SZE YU WANG – NOVEMBER 23RD, 2020

EDITOR: RAINA ZHAO

On September 30, the two candidates for the president of the United States faced off in an ugly, chaotic debate. As Trump and Biden traded blows, a common theme emerged—both candidates took turns criticizing each other for being soft on China. Trump’s China trade policy is fairly evident. Over the past four years of his presidency, his aggressive rhetoric and penchant for tariffs have set a hostile and distrustful tone for US-China relations. Biden’s stance on China is slightly more ambiguous. Critics have associated him with the political establishment that allowed China’s ascendence into a global economic powerhouse, while others cite his recent campaign messaging as an indication of his transformation into a “China Hawk.” Will a Biden presidency “reset” US-China trade relations, or will the US continue to maintain a hard line on China? Examining the United States’ China policy during the Obama-Biden presidency can offer us some insight into Biden’s perspectives on Chinese trade.

“Soft on China”?

US-China economic relations during the Obama-Biden administration were a continuation of past administrations’ approaches to Chinese trade and human rights. The supposed connection between economic liberalization and democratic progress drove the US to seek deepened engagement with China. Early in his presidency, Obama agreed to initiate the Strategic and Economic Dialogue (S&ED) with Chinese president Hu Jintao, which provided a platform for both sides to discuss topics related to economic relations.

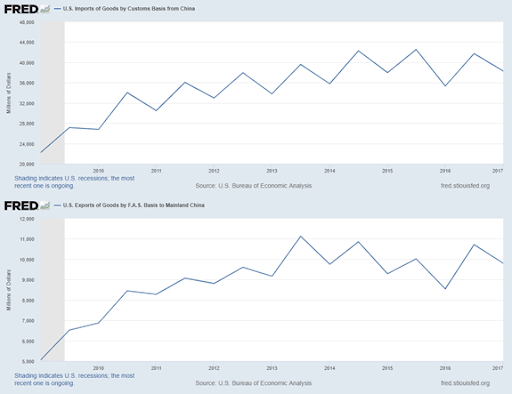

S&ED engagement led to cooperation in issues such as intellectual property rights, air pollution, bilateral air services, and bilateral investment. The two sides began negotiation on the Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT), which aimed to remove the Chinese government’s restrictions on foreign companies and eliminate barriers for US companies investing in China. These positive moves mirrored a steady growth in the volume of US-China trade. From the first half of 2009 to the second half of 2017, imports from China grew from approximately $22 million to more than $38 million, while exports to China grew from $5 million to just under $12 million.

U.S. Imports from China and Exports to China 2009-2017

Image source: FRED (Imports, Exports)

As his term progressed, however, the Obama-Biden administration shifted from a focus on bilateral economic relations to a new strategy of “rebalancing” towards the Asia-Pacific by strengthening traditional alliances and seeking out new strategic and economic partners in the region. China’s increasing aggression in the South China Sea introduced friction to the US-China relationship, and Obama-Biden policy thus grew to include an emphasis on both cooperative and hedging strategies. The US assured that it was not seeking to “contain” China, but its desire to hedge against China’s regional assertiveness also revealed a more cautious assessment of China’s growing economic and diplomatic influence. After all, “you cannot build a relationship on aspirations alone,” as Secretary of State Clinton wrote in the Foreign Policy magazine. Perhaps the biggest demonstration of US support for Asian multilateralism was the negotiation of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a proposed trade agreement between 12 countries that border the Pacific Ocean. The agreement, of which Biden was a major advocate, sought to strengthen economic ties, cut tariffs, and increase trade between member countries.

Compared to the United States’ relationship to China today, Obama-era policies were optimistic, to say the least. The US believed that it could effectively cooperate with China on trade-related issues, while minimizing their bilateral differences and balancing economic relationships in Southeast Asia.

A Changed China

Biden’s stance on China during the Obama administration was likely based on the belief that China’s leaders, including new president Xi Jinping, would continue on the path of market-liberalization. In 2014, Xi proclaimed “we shall proceed with reform and opening up without hesitation.” Instead, China has moved in the opposite direction. Promised economic reforms in areas of trade, competition policy, and cross-border investment have shown little to no progress, while plans to liberalize currency trading and capital markets have been reversed. Internet and media censorship have become more pervasive, and a counterterrorism law introduced in 2015 requires foreign technology firms to hand over sensitive data to Beijing. These changes reflect the Chinese government’s growing belief in the economic model of an all-powerful party-state, something that has been accompanied by an unmistakable trend of political centralization—Xi demands strict adherence to the party ideology, calling on party members to consolidate their “Marxist positions and ensure that the entire Party maintains a high degree of ideological and political consistency.”

The China that Biden would face today is no longer the same as what it was in the late 2000s and early 2010s, and over the past 12 months, Biden’s stance on China has shown a corresponding change towards a more confrontational approach. In May last year, Biden brazenly dismissed the China threat, saying, “China is going to eat our lunch? Come on man.” Since then, however, Biden’s messaging has undergone a tectonic shift. His campaign has begun pushing a “tough on China” narrative, using political ads to blame “the Chinese” for unemployment and COVID deaths in the US. Biden has also become more outspoken against human rights and democracy issues in China. In February, he called Xi Jinping a “thug” for having “a million Uighurs in concentration camps,” and in July, he said that he would “impose swift economic sanctions” if Beijing “tries to silence US citizens, companies, and institutions for exercising their First Amendment rights.” These comments suggest Biden’s growing perception of China as a hostile competitor.

“Buy American” vs “America First”

Despite criticizing President Trump’s trade policy, the reorientation of Biden’s stance on China suggests that he may keep Trump’s tariffs in place, at least for a while. “I think there is a broad recognition in the Democratic Party that Trump was largely accurate in diagnosing China’s predatory practices,” said Kurt Campbell, a senior advisor to the Biden campaign. In addition, based on Biden’s campaign policies, both candidates seem to have converged in their positions regarding punishing unfair trade and protecting manufacturing jobs. Biden’s promise that the future will be “made in all of America” by all of America’s workers, bears a striking resemblance to Trump’s vows to bring back US jobs.

Unlike Obama, who believed that some manufacturing jobs “just are not coming back,” Biden’s campaign website claims that he “does not accept the defeatist view that the forces of automation and globalization” will render the “vitality of US manufacturing as a thing of the past.” His “Buy American” scheme promises a $400 billion investment in US-made clean energy and infrastructure. Citing the threat of China overtaking American technological superiority, Biden has also advocated for the US to compete for global leadership in advanced technologies. To counter China’s “Made in China 2025” plan, Biden’s campaign proposes a $300 billion investment in R&D for high-tech sectors, such as 5G and artificial intelligence. If anything, these policies are likely to heighten, not ease, US-China trade tensions.

Where Trump and Biden differ is in Biden’s willingness to work with international allies to reduce economic dependence on competitors such as China. Biden similarly hopes to stand up to the Chinese government’s trade practices and “insist on fair trade,” but contrary to Trump’s isolationist views, he seeks a “coordinated effort to pressure the Chinese government and other trade abusers.” Although Biden has clarified that, as it stands, he would not rejoin the Trans-Pacific Partnership, his overall rhetoric mirrors Obama-era policies of hedging against China’s growing economic dominance by rebalancing towards Asia. “We make up 25% of the world’s economy, but we poked our finger in the eyes of all our allies out there. The way China will respond is when we gather the rest of the world,” Biden said in August.

It is safe to say that the level of healthy economic cooperation enjoyed in Obama’s early years will not return under the current climate of US-China tensions. Xi Jinping’s reversal of economic reform and continued suppression of human rights in Hong Kong and Xinjiang have shattered the hope that Chinese economic liberalization would lead to democratic development. What remains to be seen is whether Biden will prioritize Chinese cooperation on global issues such as climate change, or follow through on his promises to protect US manufacturing jobs and confront China’s unfair trade practices.

Featured Image Source: Axios

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.