SARA BETTS – APRIL 25TH, 2022

EDITOR: ZACHARY HAGEN-SMITH

If you are a regular news consumer like I am, it can feel impossible not to be overwhelmed by the perceived terrible state of the world. If you see a dramatic local news story about a car theft in your area, it may cause you to feel anxious and vulnerable as you go through your day because the instance is fresh in your mind. You may even start obsessively searching for crime-related news in your area, forgetting everything else you saw on the news that morning. In reality, your chance of having your car stolen isn’t any higher than it was before you watched the news. Salience bias describes our tendency to focus on items or information that are more noteworthy while ignoring those that don’t grab our attention. In economics, market failure happens when there is an inefficient distribution of goods and services in a free market. The 24-hour news cycle is a market failure — it intensifies salience bias, which results in the inefficient distribution of information to the public. News consumers are naturally drawn to stories that are intentionally crafted by news outlets to be enticing. This isn’t to say that the big stories we see on the news aren’t important. They are! Rather, in the words of Jon Stewart, news outlets are “elevating the stakes of every moment” and putting the public in the “information blast zone,” and this causes a breakdown in information dissemination. We are all prone to salience bias.

In June 1980, CNN became the world’s first 24-hour news network. This shift away from traditional news — where people wait until a designated time to catch up on stories — created a phenomenon that behavioral economists dubbed “the CNN effect”: the theory that 24-hour news outlets influence the general political and economic climate. Let us look at our previous example: if everyone in your city saw the news story about the car theft, the heightened sense of worry could cause a ripple effect. In the next election, a mayoral candidate may run on a tough-on-crime policy, securing them the win and affecting the crime policy in your city moving forward. Today, there are nearly 3,100 newsrooms in the United States, each of which produces stories regularly. Because media outlets provide ongoing coverage of a particular subject matter, viewers’ attention becomes narrowly focused for prolonged periods. This increased attention can affect the market values of companies that find themselves in focus and cause individuals and organizations to react to the covered subject matter in ways that they would not have otherwise. As a result, news outlets play a leading role in influencing policymakers and event outcomes.

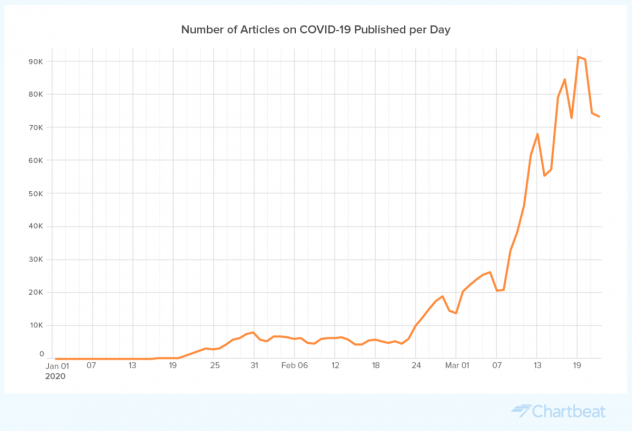

Image Source: Chartbeat

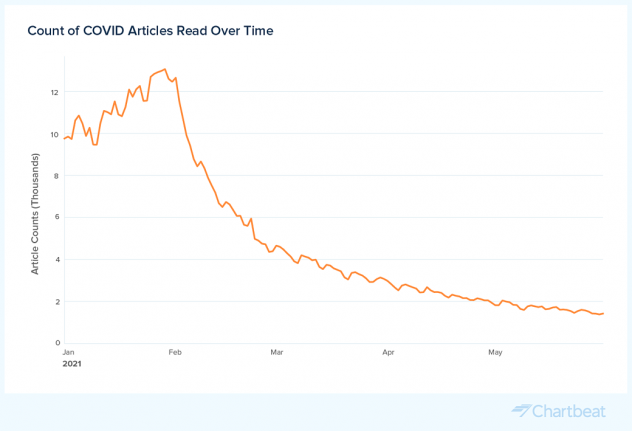

Image Source: Chartbeat

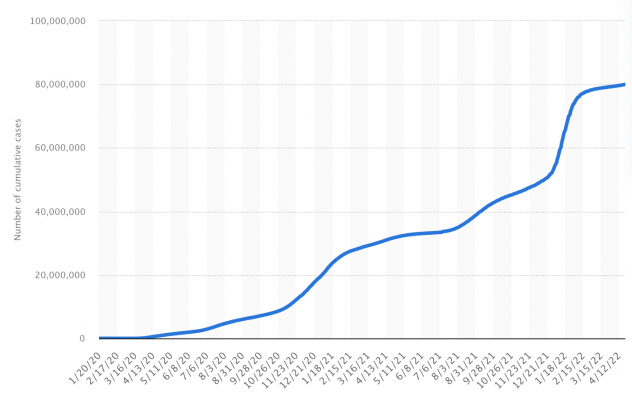

As shown in Figures 1-2 (above), the total number of global COVID articles declined by 63% between January 31 and May 1, 2021. Meanwhile, the amount of COVID articles read over the same period plummeted by more than 93%. However, the cumulative number of COVID cases in the United States during this period steadily grew (shown in Figure 3 below). There were over 25 million cases as of January 31, 2021, and over 32 million cases as of May 1, 2021, which is a 23.7% increase. This is a clear indication that news coverage directly influences what people care about at a given time.

Source: Statista

This phenomenon has multiple drivers: stress and demand, private interest groups and dark money, and ideological congruence.

Stress and Demand

High-stress situations raise the demand for news coverage. Research after the 9/11 attacks found that adults watched, on average, eight hours of event-related coverage in the days immediately following. Similarly, as news coverage on COVID increased between January 1 and March 19, 2020, so did the internet traffic on the topic.

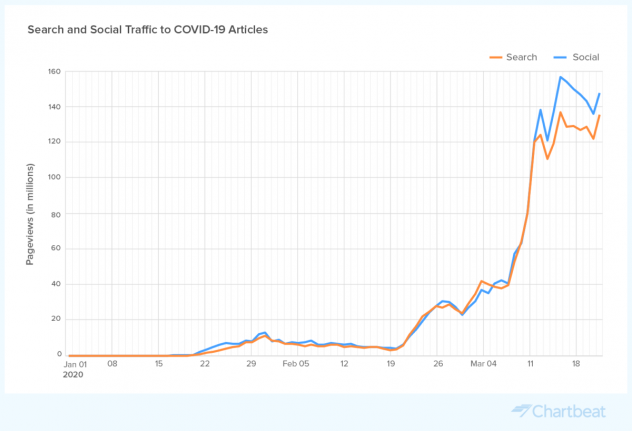

Source: Chartbeat

Figure 4 (above) shows a drastic jump in traffic around March 11, 2020, the day when the World Health Organization declared COVID to be a pandemic. The number of COVID cases between March 10 and March 11 did not increase drastically, but after the announcement, schools and restaurants began closing, offices started opting for remote work, and we were all thoroughly shaken. I was working in an office at the time, and on Monday, March 9, we were all (begrudgingly) ready for another normal week of work. On Friday, March 13, we went remote, and I spent the next few weeks obsessively checking the case count for where I lived. COVID already existed on March 9. This is an example of salience bias.

Private Interest Groups and “Dark Money”

“Dark money” refers to political spending by donors whose sources of wealth are unkown. This is a key player in our situation. Without understanding the active work being done to influence public opinion, it is impossible to fully understand the salience bias issue in the news. Research suggests that advertising funded by dark money can “amplify existing resentments and anxieties, raise the emotional stakes of particular issues or [bring] to the foreground some concerns at the expense of others, stir distrust among potential coalition partners, and subtly influence decisions about ordinary behaviors (like whether to go vote or attend a rally).” In doing so, it increases salience for chosen topics by exploiting the emotions of news consumers.

Private interest groups use dark money to achieve their objectives through advertising. These advertisements are fed to consumers in true 24-hour news cycle fashion, especially during election years. Nonprofit, tax-exempt groups organized under section 501(c) of the Internal Revenue Code may engage in varying amounts of political activity. Because they are not “political” organizations, they are not required to disclose their donors publicly. Since they don’t coordinate with political parties or candidates, they are allowed to raise unlimited sums of money from individuals, organizations, and corporations. There are several types of 501(c) organizations with different structures, uses, and capabilities (outlined below). None of these organizations are required to publicly disclose the identity of their donors or sources of money, though some disclose funding sources voluntarily.

There are 501(c)(3) organizations, which exist for religious, charitable, scientific, or educational purposes. They are not supposed to engage in any political activities, though some voter registration activities are permitted. Donations to these groups are tax-deductible. Some examples include the NAACP, the Center for American Progress, the Heritage Foundation, and the Center for Responsive politics.

Next are 501(c)(4) organizations, the most common type of dark money group. Often referred to as “social welfare” organizations, they are allowed to engage in political activities as long as those activities do not become their primary purpose. It is important to note that the IRS has never defined what “primary” means in this context, nor has it said what the methods of calculating percentages are, so the current de facto rule is 49.9 percent of overall expenditures. Donations to these groups are not tax-deductible. Some examples include the National Rifle Association, Planned Parenthood, Majority Forward, and One Nation.

501(c)(5) organizations are labor and agricultural groups that are allowed to engage in political activities as long as they adhere to the same general limits as 501(c)(4) organizations. They are generally funded by dues from union employees. Donations to these groups are not tax-deductible. Some examples include the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), and the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME).

The last are 501(c)(6) organizations, which include business leagues, chambers of commerce, real estate boards, and trade associations. They are allowed to engage in political activity as long as they also follow 501(c)(4) limitations. Donations to these groups are not tax-deductible. Some examples include the US Chamber of Commerce, the American Bankers Association, and the National Association of Realtors.

OpenSecrets — an independent, nonprofit research group that tracks money in U.S. politics — notes that “there is no way to systematically track all political spending by 501(c) organizations. Groups often use loopholes in the FEC regulations to buy web ads, mailers, and, in particular, large amounts of television ads for which there is no reliable data.” However, it is estimated that dark money groups spent roughly $1 billion, with the top organization alone donating over $125 million, to influence elections in the decade since the 2010 Citizens United v. FEC ruling that gave rise to private interest groups. Voters who are barraged with political messages paid for with money from undisclosed sources may not be able to consider the credibility and possible motives of the wealthy corporate or individual funders behind those messages. The people who fund these messages choose what has salience for general consumers and are therefore contributing to the overall problem. The top-funded messages are shown the most often and become the most salient, which is when market failure happens.

Ideological Congruence

Ideological congruence describes the proximity between citizen ideology and representative ideology. Simply put, people like representatives with similar values and opinions to their own. Research shows that ideological congruence is positively correlated with the salience of issues. People on either side of the political spectrum are more likely to share news that aligns with their beliefs, creating echo chambers of salient information.

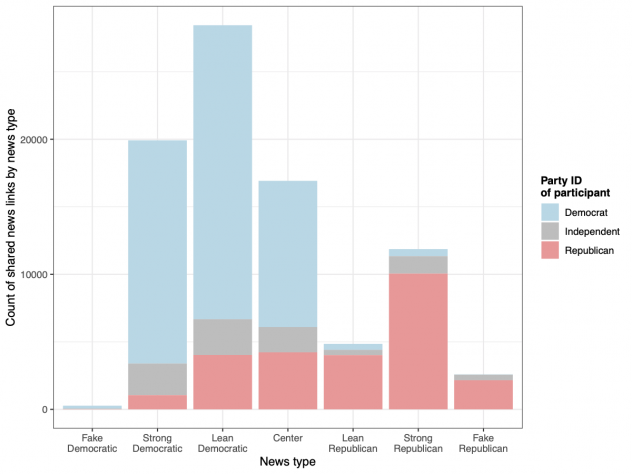

Rampant social media news sharing is a direct result of the 24-hour news cycle. In 2021, The Brookings Institute conducted a study on the impact of partisanship on sharing fake news. They found that the sharing of heavily biased and false news stories is a bipartisan phenomenon. There’s a high occurrence of heavy bias in news sharing, regardless of party preference, which is shown in Figure 5 (below).

Source: The Brookings Institution

I asked three people, who all have different political ideologies, why they watch or do not watch the news, and I received various answers, from “I don’t watch the news because I feel like if something important happens, someone will tell me,” to “I don’t watch mainstream news outlets at all because I feel that they are not factual and have an agenda, which is why many are in sync with each other […] many times, it has to do with who owns the outlets. I want to know that the news I am watching is evidence-based,” to “News these days is all so biased and polarized to appeal to certain political demographics. I try to only get really invested in stories that I have enough info on, whether from all perspectives or the rare, unbiased article.”

All three answers are examples of how ideological congruence affects salience. In the case of the first answer, the respondent is relying on people in their social circle, who likely share similar beliefs, to relay information that they deem essential. In the second, distrust of major news sources is causing them to engage with sources that could have a higher level of partisanship. In the third, the desire to mitigate bias creates demand for news with many perspectives, which most often only comes to fruition for highly-covered topics. Each of us likely falls into at least one of these categories.

Salience bias affects everyone, regardless of intelligence or political preference. The 24-hour news cycle causes an inefficient distribution of information throughout general society that can hold important policy implications, and there is no straightforward remedy. The first step toward overcoming this market failure is to recognize its existence — only then can we move forward with solutions.

Featured Image Source: Village of Crestwood

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.