VASANTH KUMAR – MARCH 10, 2021

EDITOR: MARLEY OTTMAN

Over the past year, two separate bills proposing housing rezoning reform entered Sacramento, the state capital of California; one failed, and one passed. The first bill, SB S112, was a statewide initiative to eliminate housing restrictions and allow for the development of high-density housing called duplexes, single units with two homes, where they had thus far been prohibited. Despite being approved by California’s State Assembly, it expired on September 1, 2020 before seeing the State Senate floor. In contrast, the second bill was a city policy that removed Sacramento’s city-wide zoning restrictions and allowed for the development of “quadplexes,” single units with four homes, where they had been previously prohibited. This revision was passed unanimously on January 19, 2021, by Sacramento’s City Council in a 9-0 vote.

This contrast is an apt representation of California’s relationship between state and local government. Because of historically loose central control from California’s state government, city and local governments are given the freedom to design and implement their own policies, this being especially true with respect to land use laws. The Sacramento decision, however, was remarkable in its own right; while similar proposals have been introduced in state and local governments across the country, the revised General Plan is the first such zoning reform to pass in California and the third to pass anywhere in the United States. Several decades in the making, Sacramento’s aggressive approach to housing deregulation is part of a much larger statewide movement as similar bills have been proposed in Berkeley, San Jose, and San Francisco. Targeting antiquated zoning restrictions, this movement seeks to address California’s housing crisis with bold reform driven by economics, not politics.

What is Zoning?

Local governments’ tight control over land use regulation began over a century ago. At the time, public regulation of private development only covered “public nuisances,” a legally vague catch-all term for obnoxious or dangerous developments that could harm the inhabitants of residential areas. Around the turn of the century, urban planners began to apportion land for “use-separation.” This was the division of incorporated territory into industrial, commercial, and residential “zones” where sectors of economic life were discouraged from commingling. The most innovative cities in this period, New York City and Los Angeles, had developed comprehensive zoning maps that prioritized the well-being of residential zones at the expense of industrial and commercial development.

However, the city of Berkeley would advance the next step of zoning that is most related to Sacramento’s landmark decision today. In 1916, Berkeley developed “single-family zones,” which required all units in such a zone to contain at most one home. Furthermore, whereas Los Angeles’s and New York City’s zoning ordinances had allowed for the development of residences in industrial and commercial zones (but not vice versa), Berkeley’s new single-family zoning laws were exclusionary. This completely prohibited any mixing of industrial, commercial, or residential developments. Such strict separation was strengthened by the Supreme Court case Euclid v. Ambler, which elevated the power of government zoning at the expense of a real estate company’s property rights. Thus, the legal precedent was set for a century-long, nationwide prioritization of single-family homes.

The gradual but consistent push towards further land use regulation is best exemplified in postwar California. It was in this period that bold revisions to the “General Plan” began to dominate urban planning. Unique to each individual city, the General Plan was, and still is, the metaphorical blueprint for a city’s urban design. Specifically, it outlines the role of zoning to enhance seven key elements: land use, circulation, housing, conservation, open-space, noise, and safety. Fueled by a flurry of supportive court decisions, cities began wielding the General Plan to support a dizzying number of regulatory forays. By the 1970s, pollution, rent control, land annexation, and, most of all, construction regulation, all fell under the purview of city governments’ so-called “zoning police powers” to improve, beautify, and manage land. This approach became even more hands-on with the introduction of “subdivisions,” which allowed cities to approve or deny developments at the individual “lot” level, which are typically only several thousand square feet. Clearly, American zoning policy offers a fascinating case study on markets that experience heavy and detailed government regulation.

Externalities, Supply and Demand, and Endogeneity

The typical economic justification for strong local government zoning power relies on externalities. Since the human cost of industrial developments (pollution, noise, etc.) is not priced into land when sold to industrial versus residential developers, zoning artificially restricts the supply of land for industrial or commercial purposes where it is most undesirable.

However, the controversial aspects specific zoning policies lie in warping supply and demand and causing heterogeneous effects on stakeholders within and without the housing market. The immediate effect of residential zoning is an increase in prices, as is empirically demonstrated in a study on Australian property. Rezoning land for residential purposes increased the price of land alone (absent any incurred construction costs) by between 30-50%, which was passed onto an equally large increase in the cost of housing. However, interpreting the cause of this price increase as a simple shift in the supply and demand curves for total housing is unintuitive. If this were the case, Sacramento’s plan to rezone single-family housing for quadplexes would be unnecessary, since the total quantity of housing (measured by area) would on net remain unchanged.

Instead, zoning acts as a constraint, not a shift, on the production and consumption patterns of three key actors: suppliers of land and construction services, homeowners, and renters. Profit-maximizing suppliers sell property to homeowners. Homeowners then choose to utilize this property for the purposes of consumption (as inhabitants) or capital investment (as landlords). Finally, renters lease this property from owners for consumption or as a cost to production (as businesses). While the effect of zoning on prices is distributed to all three actors, it only directly constrains land/construction suppliers and homeowners by limiting two factors: the quantity of land that is zoned for housing (through lot size), and the density of that land (e.g. building height gaps, the maximum number of units per lot). Single-family zoning is the most restrictive of all in this regard.

As a comparison, given a $1 million lot of land with a single-family detached home, a construction company could resell the property, build three one-unit townhomes, or build a six-unit condominium on a single lot of land. The resulting profit difference to the company, absent any zoning restrictions, would be significant: ~$220,000 for three townhouses and ~$250,000 for the six-unit condominium. As such, single-family zoning presents a significant constraint to construction companies’ profit-maximizing behavior, and artificially reduces otherwise profitable three- or six-unit buildings. The ultimate effect is a ceiling on the total quantity of dense housing—housing that is typically demanded from renters, not homeowners. Consequently, while typical zoning policy does increase the price of housing in aggregate, the higher price will nearly always be passed onto renters.

Perhaps the most important attribute of a complete zoning model is that of “endogeneity,” that being, that the implementation of certain zoning policies will itself have an impact on the future consideration of said policies. Endogeneity is a quality specific to zoning models that segment housing by class. In such models, homeowners are protected by single-family zoning from the competitive effects of low-cost housing intended for renters, consequently preventing the construction of new, more affordable housing.

This affects future zoning policies in two ways. First, current homeowners, living in desirable zones, have an incentive to vote against rezoning, in an effort to try and protect their home’s value. This restricts further construction of comparable single-family homes, which in turn prevents prospective buyers from shifting demand to new developments instead. Second, homeowners have a political motivation to restrict local immigration to preserve “community control” over zoning laws. As such, they will often vote against any laws encouraging local immigration, including rezoning initiatives that might otherwise service new residents. So, maintaining restrictive zoning laws are not only in the economic interest of the homeowner, but they also help preserve homeowner power over such laws. This positive feedback loop ensures that zoning laws are preserved to benefit the homeowners, or class of homeowners, that existed at their inception.

California’s Housing Crisis

Understanding this model of zoning is of paramount importance to deciphering California’s current housing crisis. By the 1970s, local governments in California had unequivocally improved the state of existing single-family zone residents by regulating traffic, pollution, noise, and, most of all, further development. However, between the 1970s and today, two gargantuan problems with single-family zoning began to appear.

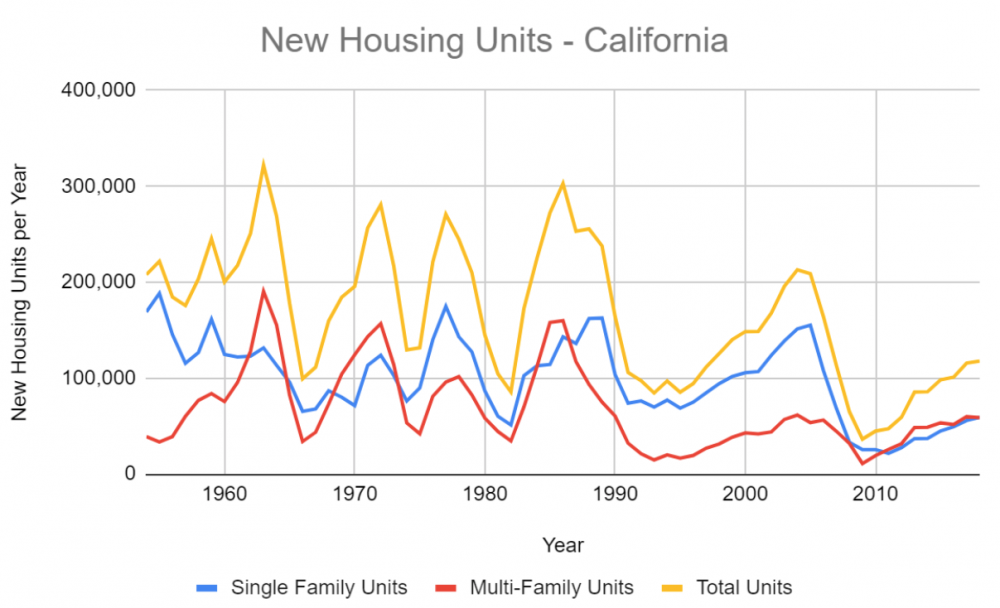

The first was slack housing supply. From 1920 to 1970, California’s population had increased from 3.4 million to 19.95 million, and infrastructure development had accelerated to meet demand for transportation, education, and housing. However, as the population continued to increase after 1970, the total level of housing construction, especially the construction of multi-family units, began to steadily decline (Fig. 1). This decline, and the statewide shortage of 3.5 million homes it ultimately created, has many origins. For example, the state legislature passed the California Environmental Quality Act in 1970, and the Supreme Court mandated the application of the act to private development, resulting in further restrictions on residential development. Additionally, natural increases in construction costs in cities also became prohibitive. Today, developing a single unit costs, on average, $146,000 more in the Bay Area, and $64,000 more in Los Angeles, relative to inland areas of California.

Arguably, the definitive factor in reducing new construction was zoning. The “tax revolt” of Proposition 13, which passed by overwhelming voter support in 1978, limited property taxes to 1% of “assessed value.” This decimated local government revenues; in response, they began to dabble in “fiscal zoning,” which is the deliberate use of zoning policies to increase tax revenue. Cities also began introducing so-called “development fees” to new construction projects in residential zones. On top of such fees, cities began to favor zoning land for commercial purposes at the expense of its potential residential uses, incentivized by greater sales tax revenue. The significant effect of such policies is highlighted by the negative correlation between zoning regulation and housing construction. In 2019, the 10 most-regulated cities in California had a 9% slack in the level of expected housing, whereas the 10 least-regulated cities had a 3% excess in expected housing (where “expected housing” is determined by the city’s housing demand and population growth).

Image Source: California Homebuilding Foundation

The second major problem with California’s zoning was inequality. Ostensibly motivated by environmental concerns, the NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) anti-development movement, concentrated in the Bay Area and Los Angeles, halted the development of new housing in urban areas through zoning restrictions on environmental impact, building height, parking requirements, and building density. The result was the creation of intensely segregated communities, which artificially constricted the natural movement of low-income renters and minorities into such areas.

The economist Raj Chetty uses communities across the country (including California cities like Encino, Hollywood, and Sherman Oaks) to show that children from low-income families who grew up in more affluent communities ended up earning more on average than their parents. Termed “Opportunity Zones,” these areas are nearly perfectly defined by single-family zones. Chetty concludes that favorable zoning offers significantly better opportunities for education and social mobility than the regions that the poor and working class are typically constrained to by protectionist zoning policies. Additionally, the sizable intersection that exists between economic inequality and racial inequality in housing was compounded by the often-racist origin of zoning policies. These were frequently implemented and justified using fear mongering about the local immigration of Black, Latino, and Chinese families into single-family zones.

While such blatant rhetoric has more or less disappeared, opposition to rezoning these historically segregated neighborhoods is still present today. In reaction to Sacramento’s groundbreaking decision to rezone all single-family zones, the Elmhurst Neighborhood Association stated:

“No one will have the ability to live in lower-density neighborhoods…The city needs to preserve existing neighborhoods in order to promote home ownership opportunities for everybody.”

As explained by the endogeneity of the economic zoning model, these socio-economically homogeneous enclaves are preserved by a strong positive feedback loop, perpetuated by the desire to maintain established homeowner control over local politics. As Sacramento implements its policy in the months ahead, this feedback loop may finally be broken.

The Prospects Ahead

The fundamental problem with single-family zoning is that it drastically overshoots in its attempt to preserve residential communities. While early iterations of zoning protected city inhabitants from industrial and commercial developments, offering substantial positive externalities to their quality of life, the introduction of more detailed General Plans and restrictive zoning policies has distorted housing supply and demand. Most of all, single-family zoning prevented the natural growth of housing to be made available to renters and potential homeowners, a phenomenon that still exists today because of fierce opposition to rezoning initiatives from current homeowners.

California’s housing crisis is caused by a large array of factors; demographic shifts, increasing construction costs, and government regulation are all partially responsible for the unsustainable increase in housing costs over the past five decades. However, there is an iron link between California’s century-long embrace of single-family zoning and its struggle to provide affordable housing, and it is solidly grounded in basic economic principles. While Sacramento may just be the first city to fully realize these principles through policy, the growing demand for local and statewide housing reform will ensure that it is not the last.

Featured Image Source: Sacramento Business Journal

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.