KAT BLESIE – MARCH 26, 2019

In 1960, the year my mother was born, almost half of all women in the United States were stay at home mothers. My grandmother, like thousands of other women in her birth-cohort, was married by twenty, had given birth to seven children by thirty, and spent all of her adult life as a home-maker. We have come a long way since then in terms of equalizing the labor market participation field, with women making up just under half of the workforce today, but women still earn significantly less labor income than men do, especially at the top end of the distribution.

The most traditional explanation for the gender gap in hourly wages points to human capital factors, like differences in education and experience. This might do the trick for explaining the gap in earnings between men and women in the 1960’s and 1970’s, but it does not offer much insight into the prevailing imbalance today. Since the turn of the century, women have reached higher levels of educational attainment than men across the board, earning the majority of bachelors, masters, and PhDs nationwide. Another explanation could be that women, overall, go into lower paying occupations than men do. Yet most economists estimate that this gap in occupation and industry accounts for only half of the gender wage gap. So why then, within the same job, do we still see men earning more than women? If we follow a pure skill-premium model, assuming no educational gap between men and women, there should be no resulting hourly wage gap between genders. This line of reasoning also fails to explain why women in high-paying jobs are currently earning less than their male counterparts who have received an equivalent (if not lower) level of educational attainment. Women make up only one quarter of the top 10% earners, less than one sixth of the top 1% earners, and less than one tenth of the top 0.1% earners.

Part of this divide can be explained by the larger fraction of time women spend doing non-market activities (and the smaller fraction of time they spend at work). Among those with children, data from the Cleveland Federal Reserve shows that females engage in much more nonmarket work than their male partners (two and half hours more per day, on average). Meanwhile, males engage in one to one and half more hours per day in market work.

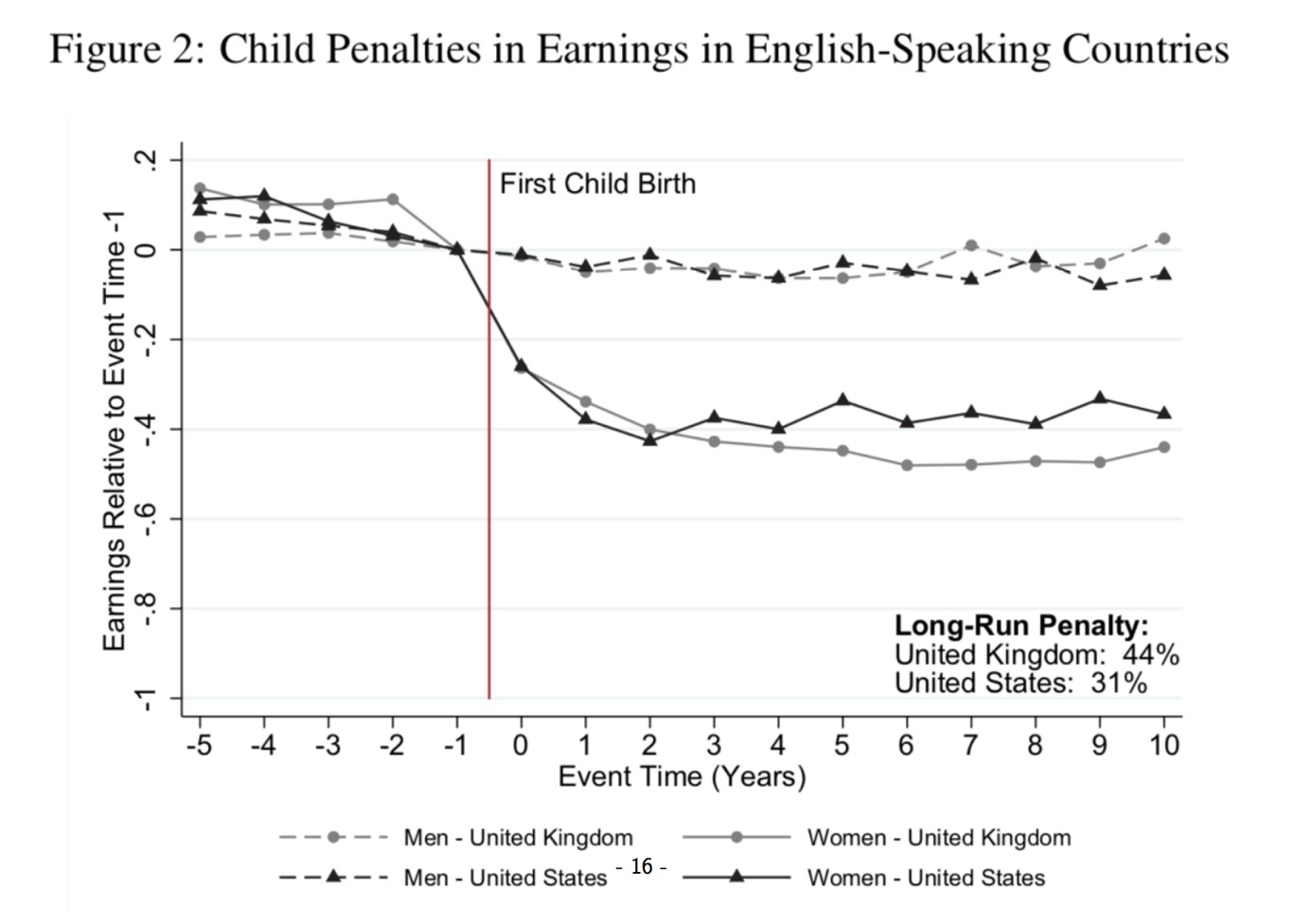

The graph above highlights the sharp decline in earnings for women after the birth of their first child. As late as ten years after their child’s birth, women are earning significantly less than their male partners are.

So why do women continue to bear most of the penalty for non-market work? Over the past decade, various research has suggested that we have not moved that far beyond the binary gender norms of the 20th century that place a woman at home and a man at work. Two independent research experiments done by Belgian economist Marianne Bertrand and by German economists Anna Wieber and Elke Host have found that women who are qualified for jobs in the highest paying sectors might be distorting their labor market outcomes to, well, make their husbands feel less threatened.

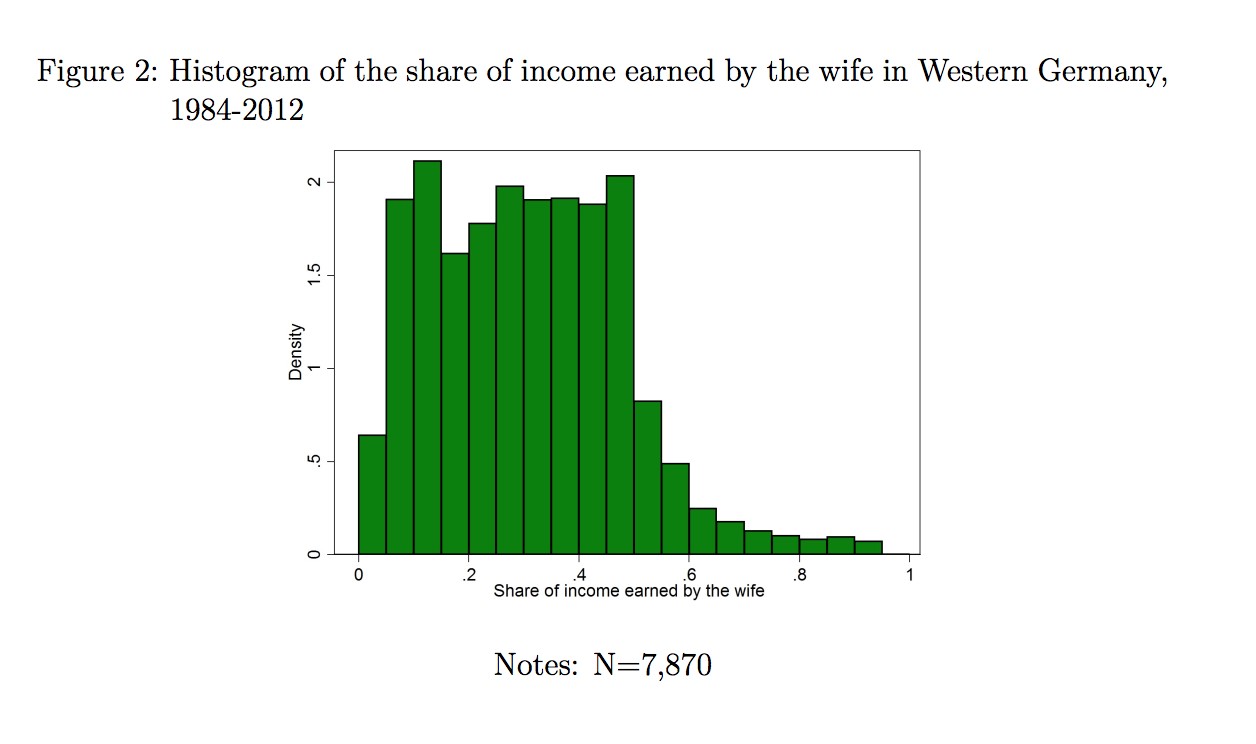

There are two arenas where this distortion may manifest itself: labor supply or non-market work. For the first, a wife whose potential income would be greater than that of her husband (based on educational attainment and occupation) may distort her labor market outcome in order not to violate identity norms either by leaving the labor force, or by distorting her earnings. Both Bertrand and Wieber and Holst found that in the United States and Western Germany, respectively, the distribution of the share of income earned by the wife exhibits an abrupt drop to the right of 0.5, where the wife’s income exceeds the husband’s income. For full time working couples, Wieber and Holst found that there is a statistically significant gap between potential and realized incomes for women who earn more than their husbands. When the probability that the wife earns more increases from 0-25 percent to 50-75 percent, the wife’s income gap increases by 4.1 percentage points; when the probability increases to 75-100 percent, the income gap increases by 5.2 percentage points, given the wife is under her potential. Moreover, Bertrand finds that an increase of the probability that the wife earns more than her husband by ten percentage points lowers the likelihood that she participates in the labor force by 1.4 percentage points.

For the second form of altered behavior, a wife who stays in the workforce and earns all of the potential income that her qualifications would predict mitigates the reversal in gender roles by putting in more hours to home production. Data for the United States shows a statistically significant positive effect on a wife’s hours of non-market work (2.8 additional hours per week) if she earns more than her husband.

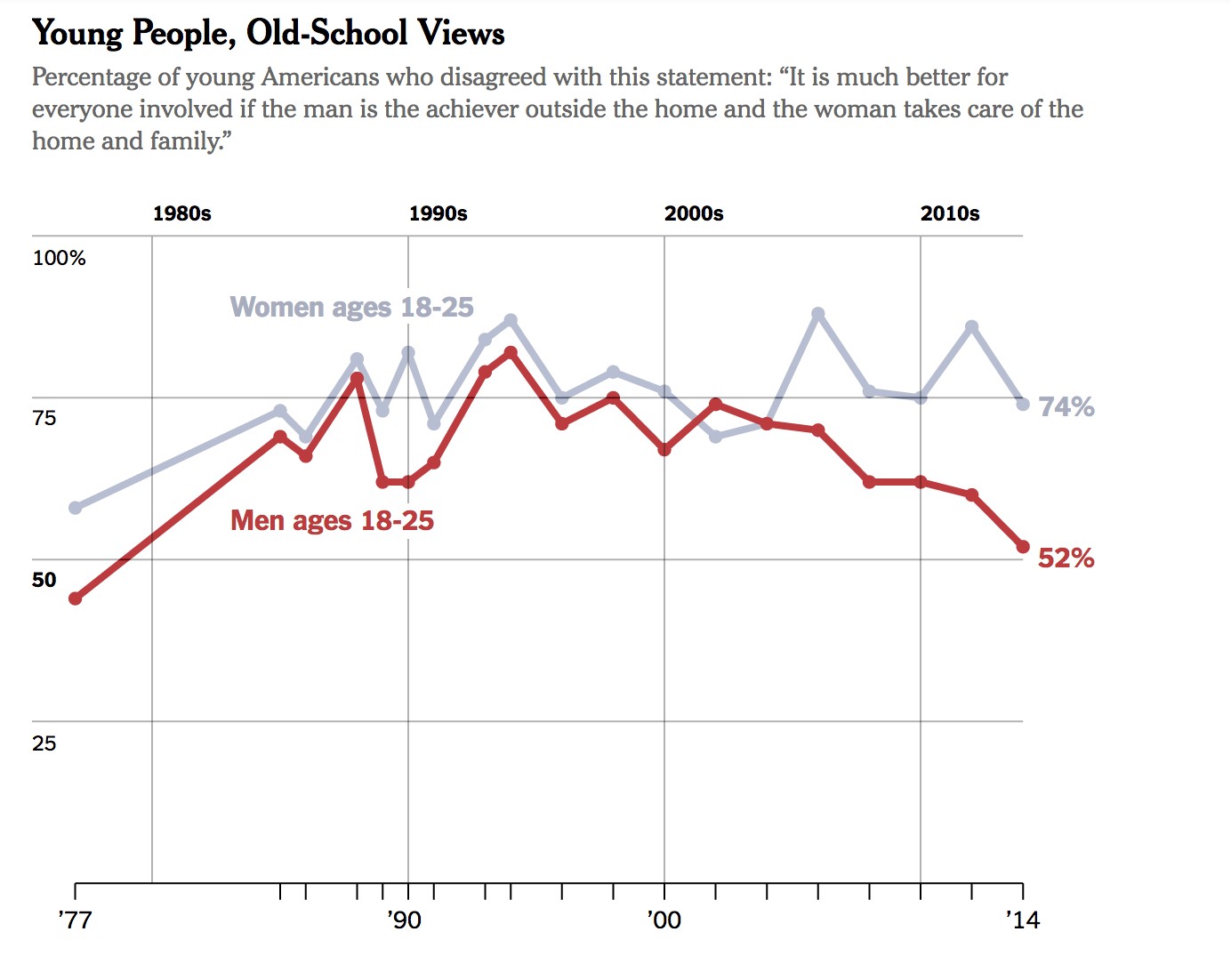

Studies like these are liable to fall victim to methodological criticisms and concerns of omitted variables. Could there be several explanatory variables that have not been considered? Perhaps, a sceptic might say, women who have married men who earn less than them are under-achieving in general, and that’s why they earn only slightly more than their husbands. Yet, when we look at opinion polls, we see the same old-school views on gender staring us in the face. In 2014, almost half of American men aged 18-25 agreed with the statement “It is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.” This number has actually gone up over the past decades, rising from only 17% agreement in the mid-1990’s to 45% agreement today.

What can explain this regression in gender-progressive thinking? Where have all the avocado-eating, leftward-leaning millennials gone? One explanation suggests a sad truth: gender norms never really disappeared. Rather, they fell dormant, and now that women are doing increasingly well in the workforce they are rearing their empirically relevant, ugly heads once again.

For many, this is a tough pill to swallow. Can our identity norms really be so slow-moving, influencing outcomes in the labor market? Or perhaps, as economists, we wonder: does a concept such as ‘identity norms’ even have a place in the study of economics? If there is any doubt regarding this second question, Rachel Kranton and future Nobel Prize-winner George Akerlof offer an economist’s point of view on why identity should be thrown into the mix. They define identity as one’s sense of belonging to social category, coupled with a view about how people who belong to that category should behave. When someone deviates from the prescribed behavior of their identity, it is costly. If there are two categories, man and woman, associated with ideas like “men work, and women stay home” and “men should earn more than women,” and if deviating from these prescribed behaviors is costly, gender identity norms can most certainly lead to lower labor force participation and lower earnings for women.

Featured Image Source: The Telegraph

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.