LEA YAMASHIRO – NOVEMBER 10TH, 2021

EDITOR: NORA GONG

Perhaps not quite as old activists foresaw, the ever-relevant, rapid mainstreaming of environmentalism had spawned a new age of consumerism. Thrift stores are the new strip malls; millions of consumers boycott corporate giants with one post on TikTok; eco-labels representing the lifecycle of everyday products take center-stage in our purchasing decisions. We’ve collectively stopped ignoring climate change, as it is no longer a future prospect, but a crisis of the present – and consumers increasingly demand that their everyday purchases align with their collective environmental conscience.

The average consumer – slowly but surely – is going green.

Many nationwide studies have verified that on average, somewhere around 50% of American shoppers are willing to pay more for sustainable products – ones that we define to provide more environmental and social benefits than their conventional counterparts. But a wholesale lifestyle change obviously proves unaffordable for many (or most), which only contributes to the decades-old gatekeeping of environmentalism as a wealthy-white-dominated movement. Sadly, in the sphere of economic elitism surrounding sustainability, there is more yet threatening to render the average individual’s perceived power of ethical consumerism completely obsolete.

—

The green-consumer consciousness shift starting in the 1990s has come with many changes to the industry from all sides of the economy. As awareness of individual environmental impact has risen, so has consumers’ desire for their purchasing power to go towards goods and services that minimize environmental harm. According to a study by public relations firm and Porter Novelli affiliate CONE, over 90% of global consumers want companies to address social and environmental issues. Consequently, companies have ascertained that with some fundamental manufacturing, distribution, and marketing changes, they could satisfy the ethical desires of their consumers and turn a profit (hence benefitting from improving their general social image). And it works – a study found that from 2013-2018, for products with visible sustainability claims, sales grew 5.6 times faster than those that did not.

But producing sustainably takes financial tolls on businesses. Why?

In the past, when calculating production costs, companies never accounted for the financial value of their environmental harm, known as “environmental externalities.” Sustainable production requires that companies actually take the cost of these externalities into account, no longer treating natural resources (and the damage done to natural ecosystems as a result of production, like waste management) as monetarily free. These higher manufacturing costs, along with higher and more ethical labor costs, in addition to a general lack of demand, results in businesses having to up their prices.

With prices increased for sustainable products, fewer people can afford to consume what they believe to be ethically and environmentally sound. A Kearney report found that sustainable products are, on average, 75-85% more expensive than conventional ones. A different Telegraph piece found that on average green goods cost around 50% more – and this checks out. In 2020, a British financial institution called Nationwide Building Society surveyed 2000 people in which 59% reported financial incapability of making eco-friendly choices in their everyday lives.

Basically, more than half of all people in developed countries like the U.K. cannot afford to “go green,” which would make sense, if the average “green” good costs 75% more. Another comparatively optimistic study conducted by CGS found that only 35% of 1000 surveyed participants would pay for a sustainable good marked up at 25% of its conventional price, confirming that well over half of the population cannot afford to make “green” choices.

—

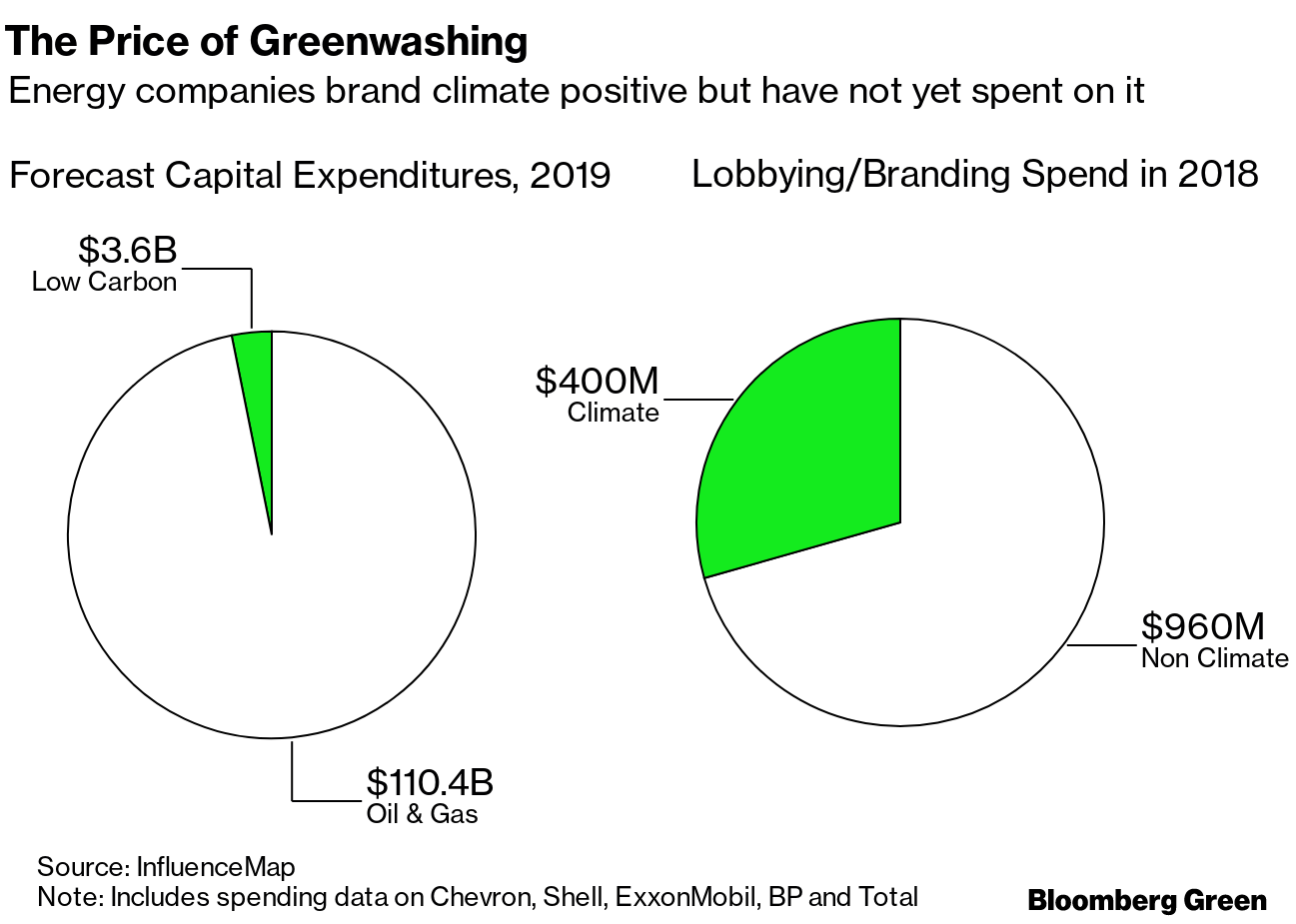

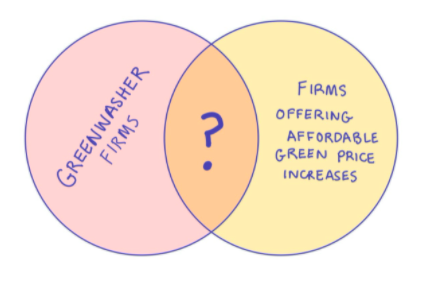

With the obvious profitability of the green market and this increase in demand for sustainable goods has also come some disappointing behavior on the part of firms who engage in the phenomenon of “greenwashing” – the act of claiming a good has environmental benefits that are untrue or inaccurate as a marketing tool to make products more desirable to the average consumer. Essentially, companies are outright lying to consumers about the environmental impacts of their investments in order to increase profitability of their products. And it’s categorically a bummer, because some companies will devote a good chunk of their budget towards sustainability advertising without making real changes. The following graphic is a demonstration of this:

Through the years, many notable companies have been accused of and proven to be greenwashing, such as ExxonMobil, IKEA, Nestle, Coca-Cola, Starbucks, and others like them. The common thread was brands marketing their goods as “carbon neutral” or “sustainable” and making similar public statements with “ambitions” and long-term goals of being 100% recyclable or “getting all the plastic bottles back.” Yet simultaneously, these companies were found having made little or no infrastructural changes in manufacturing to offset or mitigate their pollution or waste. The claims proved baseless and performative; they were reaping the profitable benefits of going green without actually going green.

In 2021, the International Consumer Protection Enforcement Network (ICPEN) conducted a global “sweep” – essentially a credibility test – of almost 500 international websites marketing goods and services identified with environmental branding – either companies marketed their goods with catch-phrases like “eco,” “sustainable,” “all-natural,” “reusable,” or had labels and logos suggesting green practices. They found that on average, 4 in 10 of these companies either a) lacked evidence to back up their environmental practice claims, b) adorned brand or eco-logos not associated with any accredited third-party certification organization, or c) were actually hiding or omitting information about company practices, like a product’s pollution levels. The European Trade Commission (ETC) conducted a similar report on greenwashing in the European Union and came to a similar result (around 42%). So, based on these reports, we conclude that almost half of all businesses claiming to be sustainable (and likely charging a higher price because of it) were either lying or lacked clear evidence to support this classification.

To recap: we have a disparity in the ability to make eco-conscious choices, and a disparity in the validity of those choices (companies engaging in the greenwash-technique take the role of fundamentally invalidating these choices.)

If sustainable goods cost on average 75% more, and 35% of consumers are willing to pay an extra 25%, then we have a minuscule amount of the population who can afford to pay, on average, for these products – as the CGS study reported, the 5% who were willing to pay for a 100% price increase.

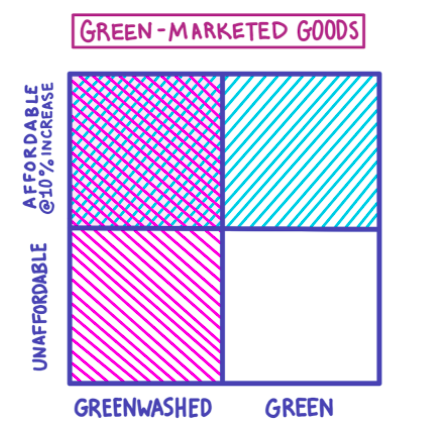

But let’s take a look at that lower 35% willing to pay an extra 25%. Following a normal distribution, we could say even 40% or 50% who are willing to pay for a 5-10% price increase. This demographic would encapsulate those for whom sustainable-consumption is generally out of reach with the exception of goods located just within an affordable price range to match their willingness to spend guided by their environmental conscience.

If we distribute the probability of the previously-discussed greenwashing evenly across all green-marketed goods (let’s just say 50/50), this 50% who are just able to afford a price hike are still, only about half of the time, going to be spending on goods whose production truly aligns with their values. The other half of the time, that extra 10% in value they paid for the “green good,” which, for the average consumer, means a lot in the long run, is not going towards a business or business practices that align with their environmental values, but rather is solely going towards the business in the form of profit, delivered on a basis of corporate lies. The greenwashing companies are therefore profiting both from sustainable marketing and irreversible environmental harm, while this well-intentioned, middle-or-lower-class consumer ends up 10% in the hole.

This leaves some questions worth further inquiry – looking at the more affordable green goods (with price increases in the 5-10% range), what percentage of the companies producing them are accused of greenwashing? I would postulate it is more than 50%, as larger companies that sell goods at lower price points have more to gain from small price increases under the guise of “environmentalism,” and probably are bigger, more powerful and can afford the potential social blow of being caught, which would likely take form as relatively only a few customers compared to their entire consumer base.

And of the companies that are indeed greenwashing, how much are they profiting from doing so? Do the majority of profits come from the more modest consumer comfortable with the 10% price increase, or from the smaller wealthy percentage of buyers willing to pay for upwards of a 100% price increase? Are companies perhaps using these metrics to target certain demographics (perhaps those with fewer resources, less education) with untruthful environmental ad campaigns knowing certain people do not have the resources to question their truth and validity?

One way we could attempt to narrow down these questions is to examine firms within the greenwashing-accused group, determine the internal factors (holding external factors such as regulation and social pressure constant), that drive them to engage in this behavior, and cross reference with the firms within this cohort offering more affordable green-motivated price increases. According to a report done at Columbia University, there are many internal drivers of greenwashing. Some are more associative (like a firm’s public history and internal guilt associated with bad pollution practices) and others can amount to varying “incentive structures” and “ethical climates.” These are defined as structures where employees at higher managerial levels are rewarded for achieving arbitrary monetary goals, and climates due to company norms with differing goals for maximization, respectively. “[Greenwashing] is more likely to occur among brown firms with egoistic, rather than benevolent or principled, ethical climates.” Egoistic firms are characterized as having “norms that support the satisfaction of self-interest.” It is not hard to infer where certain well-known corporations might fall on this scale of ethics and incentive structures.

One way we could attempt to narrow down these questions is to examine firms within the greenwashing-accused group, determine the internal factors (holding external factors such as regulation and social pressure constant), that drive them to engage in this behavior, and cross reference with the firms within this cohort offering more affordable green-motivated price increases. According to a report done at Columbia University, there are many internal drivers of greenwashing. Some are more associative (like a firm’s public history and internal guilt associated with bad pollution practices) and others can amount to varying “incentive structures” and “ethical climates.” These are defined as structures where employees at higher managerial levels are rewarded for achieving arbitrary monetary goals, and climates due to company norms with differing goals for maximization, respectively. “[Greenwashing] is more likely to occur among brown firms with egoistic, rather than benevolent or principled, ethical climates.” Egoistic firms are characterized as having “norms that support the satisfaction of self-interest.” It is not hard to infer where certain well-known corporations might fall on this scale of ethics and incentive structures.

Let’s take a company like Coca-Cola, for example, a historic multinational firm currently valued at around $230 billion (Coca-Cola has been accused of greenwashing.) The average 6-pack of Coke drinks costs $2.67. At a human population of almost 8 billion, each human consumes at least one Coca-Cola product every 4 days. Recent data states that adults with under $10,000 in their bank accounts make up 53% of the global population. It suffices to say that the average consumer in that 53% can afford to buy a coke or even a pack. Now let’s say Coca-Cola implements a 3% price increase on their average $0.99 coke due to what they claim is a supply-chain switch-up that rendered their production practices for all cokes in the world more “environmental,” and brand it as such; in this situation, consumers of all income brackets could feel just that much better about what they were buying – it’s not a lot, but it’s meaningful.

Let’s take a company like Coca-Cola, for example, a historic multinational firm currently valued at around $230 billion (Coca-Cola has been accused of greenwashing.) The average 6-pack of Coke drinks costs $2.67. At a human population of almost 8 billion, each human consumes at least one Coca-Cola product every 4 days. Recent data states that adults with under $10,000 in their bank accounts make up 53% of the global population. It suffices to say that the average consumer in that 53% can afford to buy a coke or even a pack. Now let’s say Coca-Cola implements a 3% price increase on their average $0.99 coke due to what they claim is a supply-chain switch-up that rendered their production practices for all cokes in the world more “environmental,” and brand it as such; in this situation, consumers of all income brackets could feel just that much better about what they were buying – it’s not a lot, but it’s meaningful.

We could expect a negligible change in demand but a meaningful increase in consumer satisfaction, both with respect to the company and with respect to themselves – ethical, environmental fulfillment for those who can afford it the least. Sure, it would only raise the price to $1.01, adding 2 cents. But with our highly-simplified numbers, Coca-Cola would be making at least $40 million more a day, just by claiming their product was more green than before. Massive corporations selling products at low price points have the most to gain from a little greenwashing. But this also means that, if greenwashing occurs with large corporations with at least the same frequency as it did in the ICPEN study, those in the lower 50% are more likely to be tricked into believing that they’re doing something positive (no matter how small) in the fight for climate change; it would mean that the majority of people being robbed of getting to truly put their “money where their mouth is” are the lowest-income people in our society. This would require further research, but we get the picture.

We already know that consumer-based environmentalism is locked by a form of economic-gatekeeping that only lets the wealthy elite make ethically, socially and environmentally gratifying consumption decisions. But for the larger portion of our society that can afford just a small amount of price change with the hopes that it is going towards protecting, preserving and ensuring the survival of our planet, an even smaller portion is being given the true, honest gratification and resolve of their money doing just that. Environmentalism was already being gate-kept by price differences in the market; greenwashing just makes environmentalism that much more inaccessible.

Featured Image Source: PNGWing

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.