Congratulations to our Spring 2021 Highschool Runner up, Angie Leung

Angie Leung – MAY 8TH, 2021

City populations have been on the decline for years, but Covid-19 may have delivered the death blow. Work-from-home has accelerated many trends from before the pandemic, perhaps none more so than the exodus of people fleeing major cities searching for more affordable living conditions. From mid-2019 to mid-2020, New York lost 126,355 residents, and California lost 69,532 residents. In contrast, less metropolitan states like Texas gained 373,965 residents, and Florida gained 241,256 residents.

A few hundred thousand people in a state of millions may not seem like a dire economic predicament. However, most of the relocating population tends to be high-income, well-educated people. In New York City, 44% of high-income individuals have considered relocating, and more than half of these individuals are working entirely from home. This is especially problematic for metropolitan economies because the top 25% of New York income earners pay around 90% of income taxes. Even those that stay behind have not been frequenting the businesses that are the lifeblood of metropolitan economies and state budgets. Cities like San Francisco and New Orleans saw over 45% of small businesses close as of 2020, and low-wage workers were most affected by the unemployment declines.

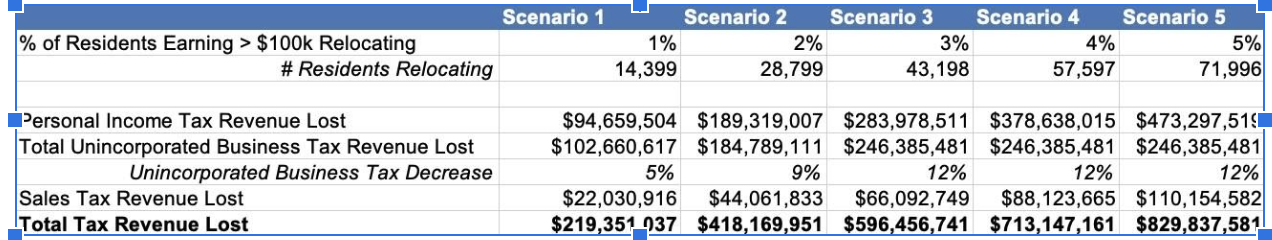

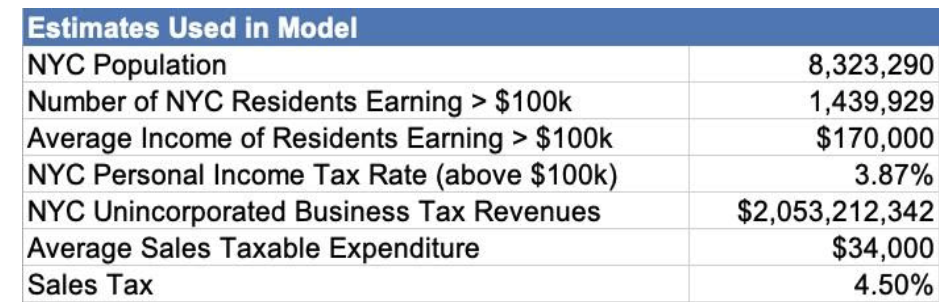

For this paper, I chose to model the impact of relocation away from New York City on tax revenue to illustrate the potential effect work-from-home could have on the city’s budget (see Appendix for more details). As relocation increases from 1% of people earning higher than$100k annually to 5%, we see a dramatic decline in estimated tax revenue, on the order of $829 million a year (enough to fund the NYC police, fire department, higher education, water supply, and economic development combined)

While New York might not reflect the situations across all metropolitan states, it reinforces the idea of a death spiral. People are leaving, but not only that, wealthy people are leaving, which significantly decreases tax revenue and long-term economic growth. With fewer resources, cities struggle to attract more people. Thus, the state government cannot invest as much, leading to a downward spiral where the lack of investment encourages more population outflow. Cities are on life support, and metropolitan areas are heading on a declining trajectory—unless cities take active steps to stem the bleeding. There are three main options cities have.

First is to entice high-skilled workers back to cities, but that is fighting against the fundamental shift in the way people work. In a survey with 1,300 CEOs, 69% of employers anticipate downsizing office space, and 73% found working remotely has widened their potential talent pool. The long-term economic impact is that fewer people will need to work in the office, no matter how much money a city invests to make working in a city more affordable.

Secondly, offer incentives for existing people who live there to stay and provide new opportunities to fill in the void left behind. For example, Governor Cuomo’s Workforce Development Initiative is investing $175 million for job training, but much more is needed to help those staying behind. Cities should try to incentivize recent graduates to stay behind with rental assistance and target high-paying industries where work-from-home is less prevalent.

Third is to concede that while people are leaving, cities can transform into lifestyle areas to attract people to support the local economy. Cities should convert existing office space into recreational, social, and retail areas that elevate the vibrancy and appeal of cities to people in surrounding areas. Better transportation will also encourage people to continue visiting the city even if they do not live there. In the long-run, the increase in sales tax revenue and the number of people staying in cities will help recoup some of the initial investments and place cities on a strategic path to remain relevant in the coming decades.

Although this essay primarily focuses on metropolitan states, the effects of the increase in remote workers are widespread. Yet the impacts of work-at-home policies are most evident in cities, where a long-term decline of tax revenue, investments, and business activity spell trouble for city economies. Despite the trajectory cities are on, the pandemic also represents an opportunity to redefine the identity of a city to transform how cities continue to attract talent and business. Work-from-home will have long-term consequences on metropolitan economies, but it is time for cities to adapt to these changes and revive themselves as vibrant hubs for the future.

Appendix:

Bibliography:

Works Cited

Ostrowski, Jeff. “Which States Are Gaining, Losing Most Population during Pandemic?”Bankrate, 12 Feb. 2021, www.bankrate.com/real-estate/states-growing-most-during-pandemic/.

Hendrix, Michael. “A Survey of New York City’s High-Income Earners: The Future of Work and the Quality of Life.” Manhattan Institute, 16 Sept. 2020,www.manhattan-institute.org/survey-nyc-high-income-earners-future-work-and-quality-li fe.

Walczak, Jared. “Taxes and New York’s Fiscal Crisis: Evaluating Revenue Proposals to Close the State’s Budget Gap.” Tax Foundation, 8 Dec. 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/new-york-budget-gap-new-york-revenue-shortfall/. Source: New York Executive Budget, FY 2021.<https://www.governor.ny.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/FY2021BudgetBook.pdf>

Routley, Nick. “Mapping the uneven recovery of America’s small businesses.” World Economic Forum, 6 Oct. 2020,

www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/10/mapped-uneven-recovery-us-america-small-business es-closure.

“January 2021 Financial Plan Detail.” The City of New York, Jan. 2021, https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/tech1-21.pdf

Schrader, Brandon. “Who Can’t Work From Home During a Global Pandemic?” State of Oregon Employment Department, 16 July 2020, www.qualityinfo.org/-/who-can-t-work-from-home-during-a-global-pandemic-.

“KPMG 2020 CEO Outlook: COVID-19.” KPMG, 23 Oct. 2020, KPMG. “KPMG 2020 CEO Outlook: COVID-19 Special Edition.” KPMG. 23 Oct. 2020. Web. 17 Apr. 2021. <https://home.kpmg/xx/en/home/insights/2020/08/global-ceo-outlook-2020.html>.

“Workforce Development Initiative.” New York State, 19 Feb. 2021, https://workforcedevelopment.ny.gov/.

Work Cited For Model:

“Tax Revenues.” Independent Budget Office of the City of New York, 2020, www.ibo.nyc.ny.us/fiscalhistory.html. Source: Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports of the Comptroller https://www.ibo.nyc.ny.us/RevenueSpending/TaxRevenue.xls

“New York City Metro Area Population by Year.” World Population Review, 2021, https://worldpopulationreview.com/us-cities/new-york-city-ny-population.

Hendrix, Michael. “NYC needs its rich residents.” City&State New York, 9 Dec. 2020, www.cityandstateny.com/articles/opinion/commentary/nyc-needs-its-rich-residents.html#

:~:text=Admittedly%2C%20New%20York%20City%27s%20tax,billion%20in%20fiscal %20year%202021.

Property Club Team. “New York City Income Tax Guide.” Property Club, 27 June 2020, https://propertyclub.nyc/article/new-york-city-income-tax#:~:text=Earning%20less%20th an%20%2412%2C000%20%2D%203.078,than%20%2450%2C000%20%2D%20%241

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.