DAVIS KEDROSKY – FEBRUARY 27TH, 2020

EDITOR: COURTNEY FUNG

In the latter half of the sixteenth century, Spain was the foremost power in Europe—a status it took less than fifty years to lose. Under the modernizing Phillip II, the ruling Habsburgs had forged an empire stretching from India to Peru, including much of Italy, Portugal, and the Netherlands. The last vestiges of Muslim authority were swept away in the Reconquista, and a Catholic-led fleet permanently checked the advance of the Ottoman Empire at Lepanto in 1571. Economically, Spain was never so prosperous either in absolute or relative terms; the wool industries flourished, urbanization increased, and a stream of galleons poured American treasure—silver from the mines at Potosí—onto European docks. The Spanish merchant marine, bolstered by Portugal’s after the two nations were unified in 1981, was tied with that of the Dutch for the world’s largest, and was triple that of rivals England and France. This was the Siglo de Oro, enlightened by the paintings of El Greco and the writings of Cervantes—an age of simultaneous political, cultural, and economic efflorescence unparalleled since the fall of Rome.

In the latter half of the seventeenth century, Spain was a second-rate nation. Serially bankrupt, war-torn, and agriculturally barren, she watched Europe’s new powers (including former Spanish territories) fight the War of the Spanish Succession for the empty throne of the childless Charles II. The problems were not just political; core export industries, especially that for wool, tumbled during the early seventeenth century as the population declined and the cities and towns, recently endowed with spectacular architecture, sank into the arid countryside. Even Spanish trade, long a driving force behind her imperial success, was no longer Spanish—at Cádiz, a primary port, only 12 of 84 commercial houses were domestic. The world’s most expansive and robust economic power had evaporated in less than fifty years. How did this happen?

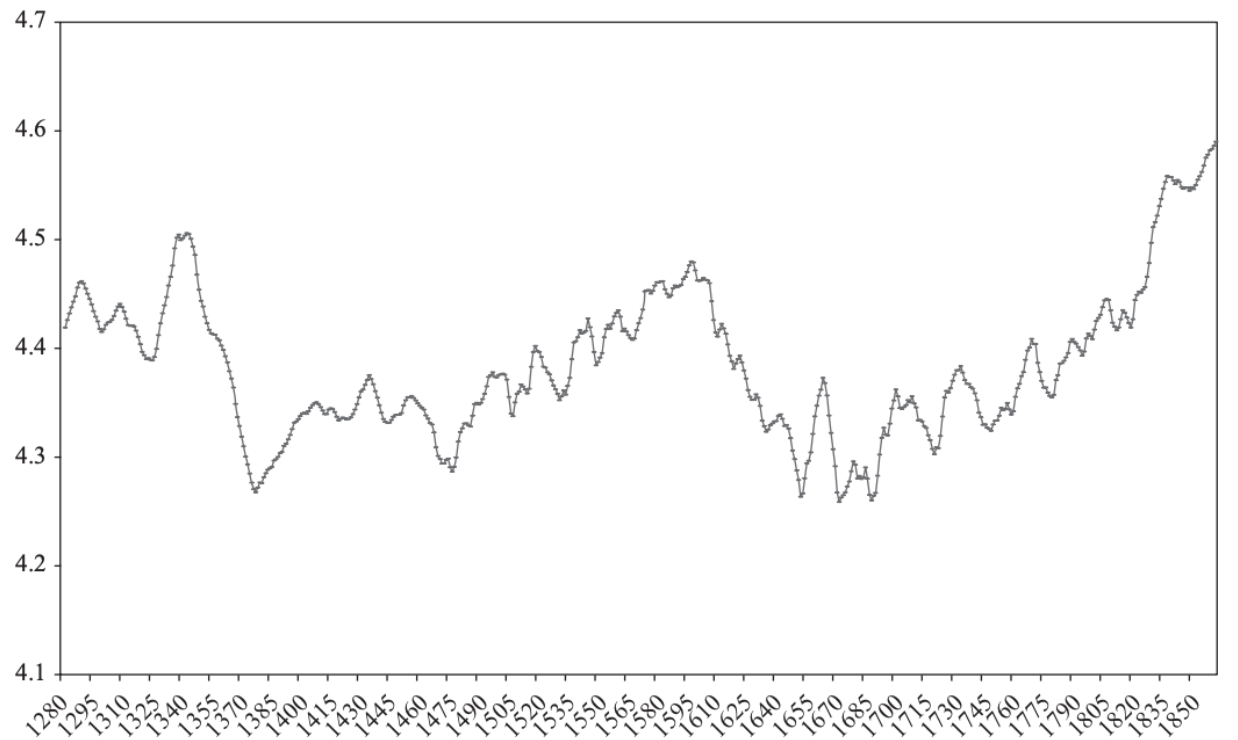

Historians, obsessed with shifts in global hegemony, have long debated the causes, timing, and severity of the Spanish collapse with literature attempting to explain these shifts dating as early as the seventeenth century. One interpretation follows a social and political narrative, tied to the repeated annihilation of the Spanish Armada, the rebellions of Portugal and the Netherlands, and failed wars with the Protestants on the Continent, all of which drained resources and transferred authority to a rising France. The problem was compounded by the incompetent successors of Philip II, who faced troubled times with illness and inadequate governance. But the chronology (ascribed to the late seventeenth century) doesn’t quite work. Spanish GDP per capita, rising through the sixteenth century, peaks in the 1590s before declining to an all-time low in 1640. Industrial and agricultural output follow similar paths, while inequality spikes. Something was clearly broken even before the reverse of political fortunes.

Image Source: The Economic History Review

Image Source: The Economic History Review

Spanish real output per capita, 1280–1850 (11-year moving averages) (1850–9 = 100) (logs) Álvarez-Nogal and Prados De La Escosura 2013

Earl J. Hamilton, an economic historian at the University of Chicago, first formulated an economic explanation for Spanish malaise in his 1934 paper “The Decline of Spain.” Documenting a total collapse of Spanish manufactures in the early seventeenth century, including a 60% decline in the number of sheep in Salamanca and a three-quarters reduction in woolen manufactures in Toledo, Hamilton proposed that a series of necessary but individually insufficient factors struck simultaneously. A combination of oppressive taxation, orthodox Church oppression, overgrazing, and an excessive focus on the accumulation of colonial silver at the expense of human capital, he claimed, had hollowed out an already-ailing regime and left it vulnerable to crisis.

An influential survey by Douglass North and Barry Weingast, later echoed by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, offered a fundamental unified cause: bad institutions. Seeking to explain the concurrent rise of Northwest Europe, North and Weingast proposed that—as opposed to England, where after the Glorious Revolution Parliament constrained royal authority—Spain’s absolute monarchy failed to offer the stability and property rights required for economic growth. So long as the lottery of birth determined the character of the national government, Spain was doomed to extortionary taxation, high interest rates, and low business activity. Conveniently, the institutional interpretation helps to explain the long-run deviation in GDP per capita between England and Spain in the years preceding the Industrial Revolution, as well as the subsequent take-off of the former. A recent paper by António Henriques and Nuno Palma disputes this conclusion, however; their data reveals that Spain’s parliament met as often as England’s during the crucial centuries, approving fewer extraordinary taxes and debasements while maintaining an unexceptional interest rate. Only after 1650, with Spain already floundering, does England boast a more active legislature.

What changed at the end of the sixteenth century, then? Quite possibly, Spanish colonial success. Global silver production rose from 2.9 million ounces per year in 1521 to an astonishing 13.6 million by 1600 after the mines of Potosi were discovered in 1545, launching an inflationary wave in Europe known to history as the “Price Revolution.” While some countries, seeing prices outpace wages, managed to profit, Spain, through which much of the importation flowed (partly by royal fiat), may have fallen prey to a malaise labeled by economists as the “Dutch Disease.” According to the theory, the flood of coin increased demand for non-tradeables (domestic goods and services) at the expense of tradeable industrial production (exports and competitors of imports). Providers of the latter, engaged in the textile, iron, and forestry sectors driving Golden Age prosperity, were forced to transfer already limited resources of labor and capital toward extractive silver production; these manufactures collapsed, as described by Hamilton. Thus Santander, which had exported 17,000 sacks of wool on 66 ships in 1572, saw only 505 bags depart on eleven ships fifty years later. No country could sustain such a hollowing-out and remain geopolitically sound. Spain did not.

As with most questions of historical causation, the most probable answer to the riddle of Spanish decline is “all of the above.” History is strongly conditional, ridden with twisted causal webs that defy unraveling, making it likely that each factor—war, taxation, borrowing, monarchy, silver—played some part. Even this explanation, however, does not include the role of human capital, an element crucial to England’s economic rise in the coming century. No individual hypothesis, however, so comprehensively explains the industrial disintegration as does the “Dutch Disease”—or, more fittingly, “Moctezuma’s Curse.” The staggering depopulation, collapsed productivity, and economic dislocation evince an underlying force acting independently of political events. Moreover, the beginning of Spain’s descent into poverty and inequality coincided with the apex of her imperial success. GDP per capita rose as the monarchy bankrupted itself in the sixteenth century, and fell as the silver flows used to pay off debts peaked.

What does the episode illustrate? For one, the ephemerality of economic free lunches, which (though they do exist) are often eaten too quickly and greedily. And for another, the fall of Spain highlights the complexity of the relationships between colonization, natural resources, and national prosperity. Extractive economies can be detrimental to both extractors and those extracted from, if not in equal measure, and imperial conquests need not beget productivity. Simplistic equations of resources with industrial triumph, common in the historical literature, are vacuous. Britain, long scorned by Rome for lacking an ounce of gold, was the birthplace of modern industry, while China and India, resource-rich and massive, lagged for two perplexing centuries. Money is not wealth, and resources are not always riches.

Spain offers an object lesson: in history as in social science, apparently obvious victories are rarely such things. The failure of the Habsburg dynasty to couple territorial expansion with a sustainable industrial policy left the Empire trailing England and the Netherlands—nations that recognized that production and trade, not loot, were the sources of modern prosperity.

Featured Image Source: The New York Review of Books

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.