SAM QUATTROCIOCCHI – NOVEMBER 28, 2022

When you hear the word socialism, what image does it conjure in your mind? Do you think of something similar to the Soviet Union? A publicly owned economy where production is planned from end-to-end rather than by disparate firms responding to market signals? Maybe your mind goes straight to a more modern vision involving strong welfare states and labor unions similar to that of the Nordic region? If so, I don’t blame you. Contemporary mainstream political and economic discourse pretty much leaves it at that. You’ve got two flavors of socialism: the autocratic failed experiments into central planning or the prosperous mixed economies of Europe which boast partially or completely socialized medicine, education, housing, etc.

This mainstream understanding leaves a lot out. Rather than a specific blueprint of any one policy or system, socialism is a movement that has existed in some form or another since at least the industrial revolution. Focusing on whether or not we consider any one country’s system “socialist,” while sometimes interesting, misses this entirely. There are good arguments over the extent to which Nordic social democracies or Soviet-Esque centrally planned economies are socialist or not. But, the fact remains that socialists of many varieties were instrumental in fighting for the establishment of both, and socialists of even more varieties had and continue to have harsh criticisms for both as well.

Following the leadership of the Russian revolution, central planning rose to prominence as the more or less official policy of the 20th-century revolutionary socialist movement. When he wrote in the 19th century, Karl Marx was incredibly focused on critiquing capitalism. In this focus, he never theorized in detail about how a socialist economy would actually function. He didn’t see it as his place to create the blueprints of the future. He did, however, write broadly about the theoretical basis for socialism. He described the socialist economy as one where production was planned based on need rather than exchange value and profit. The Soviet Union’s implementation of Central Planning was their interpretation of this idea. World War Two required a rapid escalation of the formerly feudal country’s productive capacity following the Russian Revolution. The Soviet Union wasn’t alone in implementing a certain level of wartime central planning. Even capitalist countries (including the United States) did this. But, they did take it way further and sought to base their entire economy around it. Under this system, a government agency would plan every good and service to be produced over a certain time period and calculate all required inputs. Workplaces, almost all of which were publicly owned, would be responsible for meeting these quotas. In pursuit of these goals, the government guaranteed employment for all rather than using a competitive labor market. For most of the country’s existence, the primary goal was a rapid investment into the expansion of the country’s industrial capacity, driven first by World War Two and then by a need to keep up with the West in the arms race.

Apart from serious economic difficulties like a lack of variety and quantity of consumer goods, the central planning experiments we saw in the Soviet Union, China, and other countries during the Cold War have been denounced by many on the left as suffering from a dire lack of democracy. Self-government is seen by many of the socialist persuasion as vital. Without democratic processes which allow the public to make production decisions, the unaccountable decision-makers become a new oppressive ruling class in and of themselves. The point of central planning was for production and government to be organized on behalf of the public interest. Without democracy, there was no way to guarantee that. The Soviet economy has been described by some on the left as “State Capitalist.” A system where the role of the capitalist had been replaced by the state bureaucrats rather than the general will of the public.

Not everyone in the socialist movement could live with these failings. Many instead opted for an emphasis on pragmatism and opposition to violent revolution. These were the social democrats of the day. Exemplified by the United Kingdom’s Labour Party, Sweden’s Social Democratic Party, and many others, they had aspirations of abolishing capitalism through reforms enacted via the liberal democratic process. Sweden’s Social Democrats even supported a policy that was designed to gradually use public funds to purchase the country’s means of production. As time has gone on, though, abolition of capitalism has fallen by the wayside as one of their goals. Responsible for the bulk of the European welfare state, the socialists in these social democratic movements prioritized the nationalization of specific sectors and industries over the abolition of general commodity production. They cared less about the immediate dissolution of the capitalist class and more about building up labor against capitalist aggression by strengthening unions. The democratic management of the economy based on need rather than profit was deprioritized in favor of creating a strong welfare state funded by capitalist production. Employment was still left up to a competitive labor market rather than universally guaranteed.

Due to this focus on reform and pragmatism, Social Democracy is sometimes criticized as having compromised to the point of no longer being consistent with the goals of socialism. Some have issues with keeping the market as the primary driver of economic activity. Others call out its preservation of the capitalist class as the facilitators of that activity. They assert that as long as capitalists remain empowered, they will never allow the socialization of the economy. Case in point, opposition from capital is what ultimately killed the Swedish plan of socialization. These socialists argue that a market economy structured around private investment where workers sell their labor for wages without any democratic input in the functioning of the economy betrays some of the primary goals of the socialist movement.

Those who make these criticisms have proposed their own visions of how to structure an economy that they hope wouldn’t suffer the same ultimate failure of the Soviet bloc or what they see as a lack of ambition from the Nordic countries. Despite not being a part of the mainstream discussion, they are desperately arguing that there is a home in the socialist tent for those who are not necessarily convinced by the popular conceptions of socialism. Their ideas are aimed at those people.

The first example of this is market socialism. This school of thought rose to prominence in leftist circles following the failure and ultimate collapse of the Soviet Union. They argue that the country made a major mistake by starting at the macroeconomic level by rapidly nationalizing everything without laying the vital foundation of democracy. In day-to-day life, they claim, the worker in the Soviet enterprise was very similar to a wage laborer in a capitalist one. They had little input over the management of their workplace or their compensation. Such a problem illustrates a fundamental objection they have with the Soviet Union: How can the workers own the means of production if the workers have so little control over anything? Market socialists don’t think social democracy is an adequate solution to this either, though. It allows the capitalist class to maintain their position of power in the economy and wield that power in favor of their political interests. Under this system, workers also have no real say in the management of the area of life they spend the most time in: their workplace. Social democracy is more about giving workers more concessions in exchange for their labor rather than giving them democratic control over their work. Market socialists think the goal should not be to place the entirety of the economy under a central plan of production but rather to give workers democratic control over the operation of their workplace. Similar to the worker cooperatives that exist under capitalism. This would form the bulk of the economy that provides consumer goods. Other aspects like transportation, health care, education, etc., would be nationalized, similar to what it is like in European social democracies. Market socialists see such a system as superior to central planning. They argue it is not feasible or desirable to plan an entire economy from the top down and that the only way to achieve socialism is to maintain a market to facilitate relations between worker-directed enterprises. Despite maintaining a market, they hope this would make the capitalist class irrelevant. Everyone would be workers and collectively be their own boss. The promise of democracy in the political sphere is brought to the economic sphere, supposedly without the risks of descending into state capitalism.

Market socialism, though, was the result of certain defeatism among leftists following the failure of the Soviet experiment. It accepts the critique that it is impossible to plan an economy without markets. Some don’t share this conclusion. They believe that we can democratically plan an economy as long as it is structured decentrally from the bottom-up as opposed to centrally from a powerful state. They argue this is necessary because they see market socialism as flawed for the same reasons as social democracy but with an added critique to accompany its version of “social ownership.” Proponents of economic planning contend that the democracy of market socialism is overrated. They argue that a worker cooperative is under the same pressures that a traditional capitalist firm is under to pursue profitability. Despite workers within a cooperative firm being treated better than they would be by a unitary boss, market socialism would look to them like capitalism but with disparate groups of workers replacing disparate capitalists. The workers wouldn’t collectively own the means of production; rather, groups of them would own chunks of it and compete with each other.

To address this, decentralized planning proponents attempt to model systems of coordination between groups, which could replace markets while also becoming more democratic. One of the most developed proposals for such an economy comes from economists Robin Hahnel and Michael Albert. Originally conceived around the time of the Soviet Union’s collapse, the model has been refined and iterated over time, with their most recent book on the subject released last year. They call the model “Participatory Economics,” and it is fascinating. They would have the economy organized into workplace production councils and residential consumer councils. The production council you belong to would simply be your workplace. The workers would manage it democratically, similarly to under a market socialist paradigm. But each person would also belong to a residential consumer council. This would consist of the people in your local neighborhood. Workplace councils are responsible for collectively proposing what they want to produce and what materials they need to produce those things over a certain time horizon, while neighborhood councils formulate similar proposals for what they want to consume. Indicative prices would be used to provide constraints and balance supply versus demand via iterative rounds of plan updates, but there would be no currency that circulates and no wealth that accumulates. The goal is for nobody to receive a directive from some central bureaucracy. Planning is instead accomplished from the bottom-up and a person only ever implements a plan they have proposed and updated through the democratic process. Councils would be organized via federations where lower councils elect a delegate to participate in the next layer. Consumer councils would escalate from neighborhood up to the national level, while production councils would go from the individual firm to an industry/sectoral level. These councils would formulate plans for things only under their purview. A neighborhood would include something like a community playground in its annual consumption proposal. A city would use a similar process to plan a public transit network. Production councils would see these proposals and be free to produce those socially necessary things. It is the production of goods and services deemed socially valuable by the planning process that yields income, which can only be used to add goods to your annual individual or neighborhood consumption plan. There is no private investment with this income. Productive assets are socially owned and used by production councils that want to produce something in demand.

Both market socialism and participatory economics are quite ambitious and nobody, even their advocates, believes they will materialize overnight. Participatory economics, however, is especially fantastical. It has been criticized by leftists of the other varieties mentioned in this piece for being overly convoluted and unrealistic. Its proponents argue that it is vital to have a vision for the future that you’re working towards to animate activism and prevent complacency. Hahnel and Albert cite many features of social democracy and market socialism as vital steps in the right direction. Beyond these broad points, there is an especially lively debate between social democrats, market socialists, decentralized planning proponents, and even some who claim they have ways to make central planning work more democratically on the technicalities of how each system would function and perhaps fail. I cannot begin to adequately summarize these debates but I hope at least some of my readers decide to give some of the participants a read. Whether you are a believer in any variety of socialism or not, it would be useful for us to start seeing it as the big tent it is rather than a monolith. The truth is that you can assume very little about a person’s prescriptive beliefs from whether they label themselves socialist or capitalist. We ought to stop pretending we can.

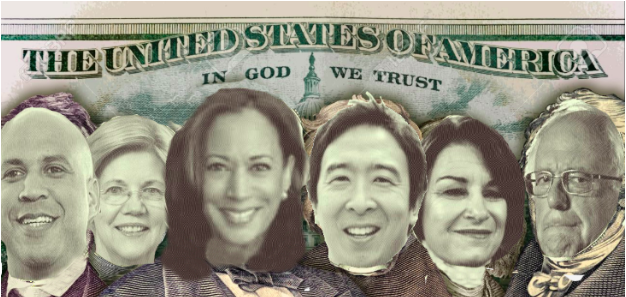

Featured Image Source: The Nation

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.