HANNAH SHIOHARA – NOVEMBER 21ST, 2022

EDITOR: KATHERINE MCKERNAN

Pay transparency, which refers to the degree of openness between a company and its employees about how much people are compensated, and the extent to which such information can be internally discussed, is garnering increased attention amongst organizations and scholars. Today, pay transparency laws have been implemented in 17 states, allowing employees to freely discuss their pay, and of these states, 8 require employers to provide salary ranges to job candidates. This movement can be seen as a commitment to narrow the gender pay gap and increase trust within the work environment, two critical factors to attract and retain top talent. However, the full effects of increased pay transparency often go unspoken. Increasing such communication can have unintended economic consequences, and can negatively impact workplace culture if not done correctly. Here are the benefits and drawbacks of increased pay transparency, and a take on how firms should go about disclosing their employees’ salaries.

The case for pay transparency

The most common case for pay transparency is that it will decrease the gender pay gap. When firms disclose salaries, they are forced to equally compensate men and women who are performing the same task as they cannot hide any information. This concept was backed up by a study conducted on Danish companies. After the 2006 Act on Gender Specific Pay Statistics was introduced, companies of 35-50 employees that were required to report gender-segregated salary data (called mandatory reporting firms) were compared to similarly sized companies that were not required to release such information (control group). Between 2003 and 2008, the gender pay gap in mandatory reporting firms shrank by 7% while there was relatively no change in the control group. The study also found that more female employees were promoted from the bottom of the corporate hierarchy in mandatory reporting firms, and that more women were being employed overall as well.

Pay transparency also makes data easily accessible, thus making it easier to identify and address discriminatory practices within the corporate realm. Agencies such as the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) rely on specific data segregated by gender, race, and ethnicity to conduct effective investigations about discrimination charges. Data that is readily available also allows advocates to reference quantitative evidence when identifying and analyzing systemic discrimination and pay gaps.

However, while these issues are critical and urgent, there is research that suggests that increasing pay transparency is not a good strategy to address and solve them. Economists have advocated against a fully transparent labor market, and case studies in real corporations have also shown negative results when communication about pay was increased.

Equilibrium effects of pay transparency

In a transparent organization, an employee can discuss their salary with their colleagues. Therefore, the rational decision for an individual to make would be to find the highest salary that is being offered to a comparable individual, and then demand that same wage. Firms now become less willing to pay for labor as they will be forced to offer the maximum wage to all employees, and thus will lower their starting wages. Since the increased chance of information spillovers compresses wages and hurts all employees, pay transparency causes an information externality.

This phenomenon is what economists call the demand effect of pay transparency: in a fully transparent market, a firm will set a maximum wage that potential laborers will either accept or reject, but in a fully secret market, a firm would be willing to give any amount of compensation asked for, as long as it is below the value of labor. The demand effect also changes how laborers approach initial wage negotiations. All laborers in a fully transparent market will ask for initial wages lower than what they would ask for if they were in a secretive market. However, those with low outside job options will lower their desired wage more than workers with high outside options, as they want to seem more attractive than other workers that would be “too expensive.” This is called the supply effect of pay transparency. Thus, in the short run period before any information spillovers occur, there will be a greater wage gap between employed workers that had high versus low external job options in a transparent company. These effects also show how increased transparency decreases an individual’s bargaining power and transfers it to the firm. In both the demand and supply effect phenomena, the firm can effectively set salaries that are “once and for all” to its workers.

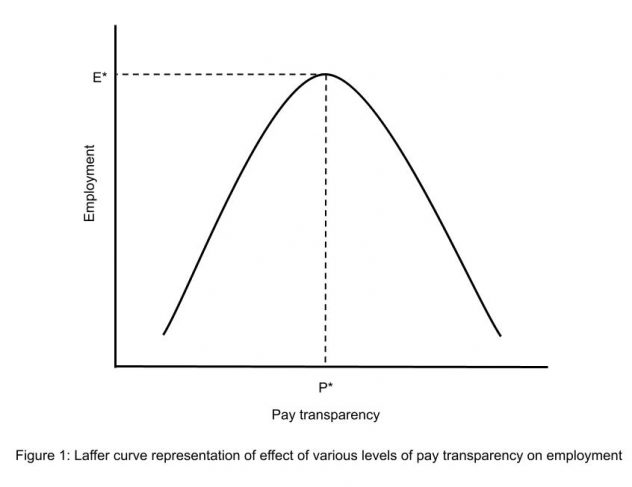

Combining the demand and supply effect, a non-monotonic overall effect in the relationship between pay transparency and expected employment level can be observed. This relationship can be graphed as a Laffer curve, as depicted in Figure 1. As transparency approaches the optimal level (P*), employment rises as the supply effect dominates. When transparency is lower, fewer workers will over-negotiate and be rejected by the firm. On the other hand, increasing transparency beyond the optimal point will cause the demand effect to dominate; the firm will reduce their highest wage faster than workers reduce their initial wage ask, leading to lower employment. The graph thus suggests that full secrecy or full transparency will minimize employment, and that an intermediate level of transparency is optimal.

Overall, examining the equilibrium effects leads to two conclusions. First, that increasing pay transparency will lower average wages, and two, that full pay transparency will minimize employment. These theories have supporting evidence, as states that have implemented the “right of worker to talk” law, which protects employees’ right to discuss their wages amongst each other, saw a 2% reduction in wages.

Dissatisfaction in Silicon Valley

Another objective of increasing pay transparency is to foster a positive work environment that is built upon trust and credibility. However, a case study conducted in two large Silicon Valley companies concluded that publicizing salaries and other pay related data may result in elevated negative emotions and employee turnover.

Take a group of 700 engineers working at Google. A large portion of their work is done in groups, and any finished products are a result of joint talent and effort. So, when each engineer is asked to assess themselves, most of them tend to overestimate their individual contributions and performance. Of the 700 surveyed, nearly 40% of them said that their performance is in the top 5% relative to their peers, and 92% of them would respond that they are in the top quarter. Based on these statistics, we can infer what would happen if everyone’s salaries were made visible to all workers. If an engineer who thought they contributed equally, if not more than another engineer sees that they weren’t earning as much, they’d think they aren’t being compensated fairly, triggering frustration and dissatisfaction. As these negative emotions heighten, the workplace would turn into a competitive space where employees begin obsessing over comparison.

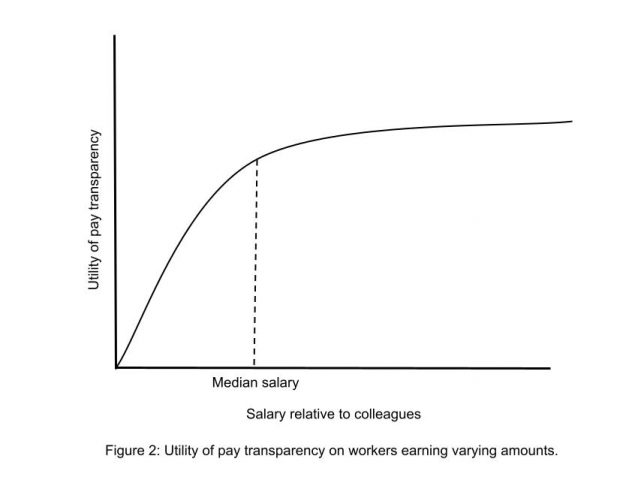

To support this line of reasoning, a study conducted by professors from the University of California, Berkeley found that pay transparency will also increase employee turnover, hurting the company in the long run. In this study, a randomly selected group of faculty at the University of California was informed of a website that listed every employee’s salaries. A couple days later, all faculty members were surveyed on their use of the website, job satisfaction and job search intentions. Almost all of the people that had been previously informed about the site had accessed it, and those that were being paid below the median rate were more dissatisfied and likely to be considering leaving their department. On the other hand, researchers found that those that were above the median rate virtually felt no effects. The research suggests that patterns of pay transparency are consistent with a utility function, where transparency has a negative impact on those earning below the median salary and provides little to no benefit for those that are past that point. This function is represented in Figure 2.

These case studies illustrate how pay transparency can cultivate a negative culture of competition and comparison among employees, going against the original objective of pay transparency.

Allocatively inefficient results

Salary disclosures may also lead to lowered efficiency within a firm. Employees that discover they are being underpaid will not put in less effort but will reallocate their effort such that they get compensated more, resulting in allocative inefficiency. This phenomenon was observed in January of 1990, when the salary of every National Hockey League player was suddenly disclosed. Underpaid players started scoring more goals but allowed their team to get scored on by more than the additional goals they provided. On the other hand, overpaid athletes played the same (they did not increase their defense), leading to an overall worse team. After the mass disclosure of salaries, players started shifting their attention from defense to offense, because those that were better at offense were receiving higher salaries in contract negotiations.

An analogous result is not hard to imagine in other business settings. For example, a teacher that is paid based on their students’ test scores may only teach students how to take tests, instead of actually teaching them important content or inspiring them. A salesperson that is paid based on commissions may focus on short-term deals and neglect building long-term relationships.

Increasing the effectiveness of pay transparency

As depicted in Figure 1, a firm that has an intermediate level of transparency is the most optimal in terms of maximizing employment. In this type of firm, though workers will learn about others’ wages stochastically after joining the firm, it is not publicized or talked about in a completely open manner. This is the point where the supply and demand effect are balanced out, such that workers still have adequate bargaining power and are not forced to accept lower average wages. An intermediate level of pay transparency seems desirable, as it would not result in negative workplace culture as observed in the two case studies and may prevent the firm from becoming allocatively inefficient.

However, pay transparency is gaining traction because the gender wage gaps and pay discrimination are urgent issues that must be addressed. There is growing consensus that the benefits of increasing transparency past the “optimal” point outweigh the costs, because it may result in a more equitable society. In such a case, there are two steps that a firm should take in order to maximize the effectiveness of pay transparency and decrease the negative results. First, along with pay information, the method that is being used to evaluate employees’ performance must also be clearly communicated. For example, implementing objectives and key results (OKRs) will provide a set of metrics that every individual can refer to assess their own work. These OKRs should be specific enough such that even employees working on highly collaborative projects—such as the 700 engineers mentioned in the Silicon Valley case study—know exactly what they did and the extent to which they contributed. By creating these metrics, employees are less likely to feel that they are being undercompensated, as they would be aware of exactly how their work and salary are correlated. Second, providing tools for professional development and supporting the growth of employees will become more crucial than ever. While employee turnover rates increase for those earning below the median salary with increased transparency, skills training programs can become the incentive they stay. In the long run, their performance will improve, and they will be compensated accordingly, benefiting them personally as well as the firm by retaining top talent.

At the end of the day, people simply want to be valued properly. Pay transparency models should be revised such that firms can uplift groups of people that have been historically underrepresented or unfairly compensated, while also maximizing their efficiency and productivity.

Featured Image Source: trupp

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.