JOSEPH NG – NOVEMBER 22, 2018

There is another side to one of the greatest economic turnarounds of the last few decades.

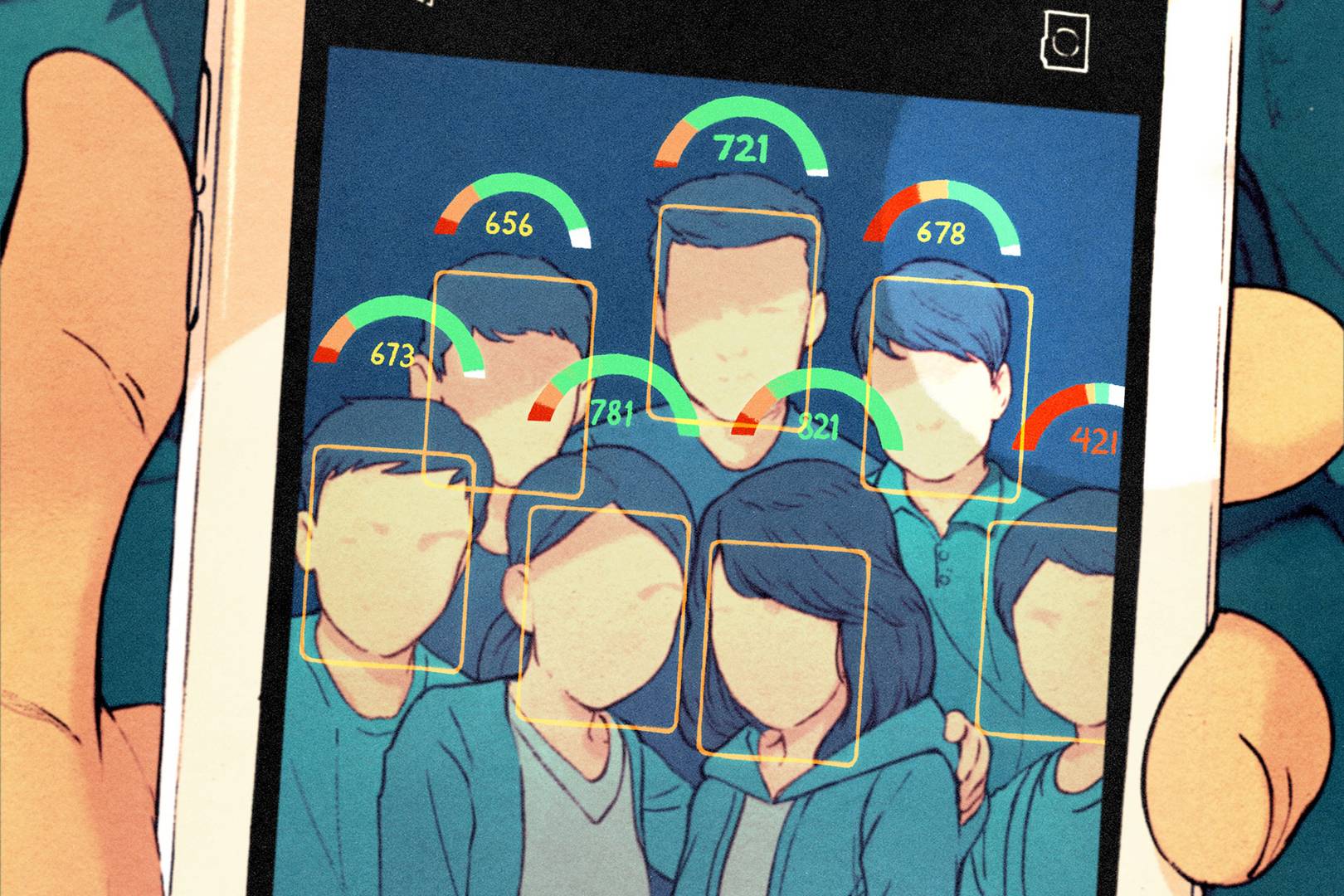

China’s rapid economic growth has meant that a fairly large proportion of citizens (about 20%, as of 2014) are not yet part of the banking system and do not have an official credit history. Many lack money, have difficulty meeting bank account requirements, or generally distrust the banking system; in some places, the financial infrastructure simply might not be present. As a result, the Chinese credit system is nowhere near as robust as that of the US, creating a problem for banks and other private lenders: without an objective score, it can be difficult to determine how trustworthy a potential borrower is.

To address this issue, the Chinese government has resorted to various measures. One, perhaps the most controversial, is the Supreme People’s Court blacklist of almost 10 million people who, for one reason or another, do not pay their debts. The consequences of being blacklisted? Being blocked from various “luxuries,” including plane or high-speed train tickets and some hotels. Some defaulters even have their faces, names, and ID numbers plastered on electronic billboards.

The government is not the only entity seeking to establish credit scores. Ant Financial, part of Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba, has established the Zhima (“Sesame”) Credit Score for users of its mobile payment app, Alipay. The program is optional, and users who opt in can receive a score based on data such as spending history (controversially, Zhima Credit’s technology director said in 2015 that buying diapers, ostensibly implying parenthood, could be considered “responsible” behavior, while video games could affect one’s score in the opposite direction). Other factors, such as the car someone drives, where they went to school, and the Zhima Credit scores of their Alipay social network contacts also factor in.

Zhima Credit has also increasingly blurred the lines between corporation and government. It has integrated the above-mentioned court blacklist, so that already 1.21 million people have seen their credit scores drop as a result of this cooperation.

Still, the program is popular. Having a high Zhima Credit score can provide access to various benefits, such as favorable loan terms. Other benefits include shorter hospital wait times, better visibility on dating sites, and the ability to rent cars or umbrellas without paying a deposit. In general, these benefits vary from city to city, depending on how much the local government has embraced these credit scores.

One city, Rongcheng, is all in.

Rongcheng, one of the pilot cities for China’s federal-level social credit score system, runs its own social credit system. Residents start with a maximum score of 1,000, and they can change their score through various actions. Receive a traffic ticket? Minus 5 points. Spreading rumors online? Minus even more. Donating blood? Positive points, depending on the amount.

Letter grades are even assigned to residents based on their scores. 960 and up is an A, and 850 to 959 is a B. 600 to 849 is a C, a warning level. Below that is a D—and the resident is labeled an untrustworthy citizen.

With a high score, Rongcheng residents can get discounts at local businesses, lower heating bills, and even some free cable channels. They also get special invitations to community events reserved for high-score citizens, and their names are displayed proudly outside city hall. If they have a low score, though, they could be ineligible for job promotions, along with other potential consequences.

One very visible result? Improved traffic safety, in a city where cars did not always stop for pedestrians.

Rongcheng’s social credit system has largely been embraced by local residents, and the response is reflective of general nationwide support of such a system. Citizens in China broadly have fewer expectations of privacy than, say, citizens of the US, and the benefits of the social credit system are many. Not only can people be rewarded for good behavior, but “bad people” can be punished. Plus, in a country where wariness of swindlers runs deep and lack of regulation has led to questionable business practices (such as counterfeit products and adulterated pharmaceuticals), social credit systems can also be used to hold businesses accountable. In one survey, 72 percent of respondents said that social credit assessments of different companies influenced their purchasing decisions. With a social credit system, each side of a transaction can have faith in the other.

There are economic considerations, however, that should not be ignored, including the potential for rising inequality. Since the benefits from social credit systems are largely concentrated in cities, wealthier citydwellers can gain more from the system than poorer rural citizens. In contrast, poorer citizens frequently lack the very resources they need to raise their scores, including education and more connected social networks. In the survey mentioned earlier, social credit systems had a higher approval rating among wealthier respondents, and urban residents were more likely to support the social credit system than rural citizens (82 percent versus 68 percent).

Additionally, those with lower social credit scores—and in the extreme case, those blacklisted by the government—have restricted access to economic resources. This makes it more difficult to raise their scores, resulting in a downward social credit spiral. Ultimately, the punishments of a social credit system could block someone’s socioeconomic mobility. As a notice signed by various government ministries and the Supreme People’s Court states, the system is built on the philosophy of “once untrustworthy, always restricted.”

The political implications of the social credit system are easy to see. In 2014, the State Council, China’s governing cabinet, released a document called the “Planning Outline for the Construction of a Social Credit System,” calling for a nationwide rating system for individuals and businesses. Each individual would be assigned a file with public and private scoring data, searchable by fingerprints and other biometric characteristics. The goal is for the system to be put in place by 2020.

For many, this vision appears alarmingly Orwellian. NPR, for instance, titled a podcast episode about social credit scores “China’s Brave New World,” a reference to George Orwell’s famous novel. And as Mara Hvistendahl of Wired writes, “For the Chinese Communist Party, social credit is an attempt at a softer, more invisible authoritarianism. The goal is to nudge people toward behaviors ranging from energy conservation to obedience to the Party.”

The idea of designated neighborhood watchers, who keep track of their neighbors’ behavior and update their scores, might put some people on edge. So too might the social credit system of First Morning Light, a small neighborhood near Rongcheng’s city hall, which has added penalties for illegally spreading religion.

Such implementations are not without some pushback. There has been resistance to the more extreme measures, especially among the older generation that still remembers the policies of the Mao era. Still, as noted earlier, the Chinese population is by and large supportive of some sort of a social credit system.

At the end of the day, the core idea of a social credit system should not seem unfamiliar. In the US, FICO credit scores based on consumer loan history are used to evaluate prospective borrowers. Airbnb and Uber ratings frequently influence user choices, and Alibaba is not the only e-commerce company tracking customer activity (Amazon, anyone?).

Still, it would be wise to watch China’s social credit experiment closely. Ratings might not be inherently evil, but the way they are used can have lasting and far-reaching political and economic consequences. Big changes could be coming to the second largest economy in the world.

Featured Image Source: Wired

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.