SZE YU WANG – NOVEMBER 26TH 2020

Professor Kim is an Associate Professor of Economics at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, and an Assistant Professor at Cornell University. His research focuses on development economics, health economics, and education economics.

Sze Yu Wang: I’d like to begin by speaking about your personal journey in economics. What was it that initially drew you to economics, and what experiences influenced this interest?

Professor Kim: I started off as a medical doctor, and I practiced for 2-3 years. One thing that really affected me was that, at the end of my time in medical school, doctors went on strike in Korea. I was shocked! How can doctors go on strike while the patients are dying? How is this possible? Of course they didn’t shut down the ER and the ICU, but this was still a shock to me. I then realized that it was to do with issues in health policy, and I saw how important public policy is.

In my last year as a medical student, I also worked at a breast cancer clinic. What I noticed was that those from rich areas with higher education and better income came in for screenings more often, and were able to afford expensive cancer treatment. For poor people, it wasn’t like that. One day, a woman came in. She looked around 65 years old, with dark skin—not dark skin from sun-tanning, dark skin from working in the sun. I looked through her documents and saw that she had been referred from a hospital in the rural area. When I touched her breast, I immediately realized that her axillary nodes were already super protruded and expanded. Anybody, even a medical student like me, could quickly realize that this was terminal cancer. But she asked me: “Do I have cancer?”

That made me very sad. She was scared, and I don’t think she could have lived long. South Korea is a pretty equal society compared to other countries, but I could see how, based on level of education and socioeconomic status, cancer survival was definitely not equal. I felt this was unfair, and I wanted to study the effects of public policy and inequality.

Think about the Chinese famine in the 1960s and 70s. Bad public policy can kill millions of people. Let’s check how many people died from COVID in the US: 234,000 people. How many people died in Korea? 400. How many in Hong Kong? Less than that. How many lives can I save as a medical doctor in one lifetime? At most 200, maybe 300. But as an economic policy-maker, the number of lives I can help is much bigger than one single doctor.

Sze Yu Wang: What research projects are you working on now, and how are you collecting your data?

Professor Kim: My research involves two types of approaches. The first one we often call primary data collection with randomized controlled trials (RCT), which is where I collect the data myself. When I was a medical doctor, randomized controlled trials were everywhere. But when I first started economics, RCT was not popular. With this approach, I may provide treatment for one group, and leave another as they are.

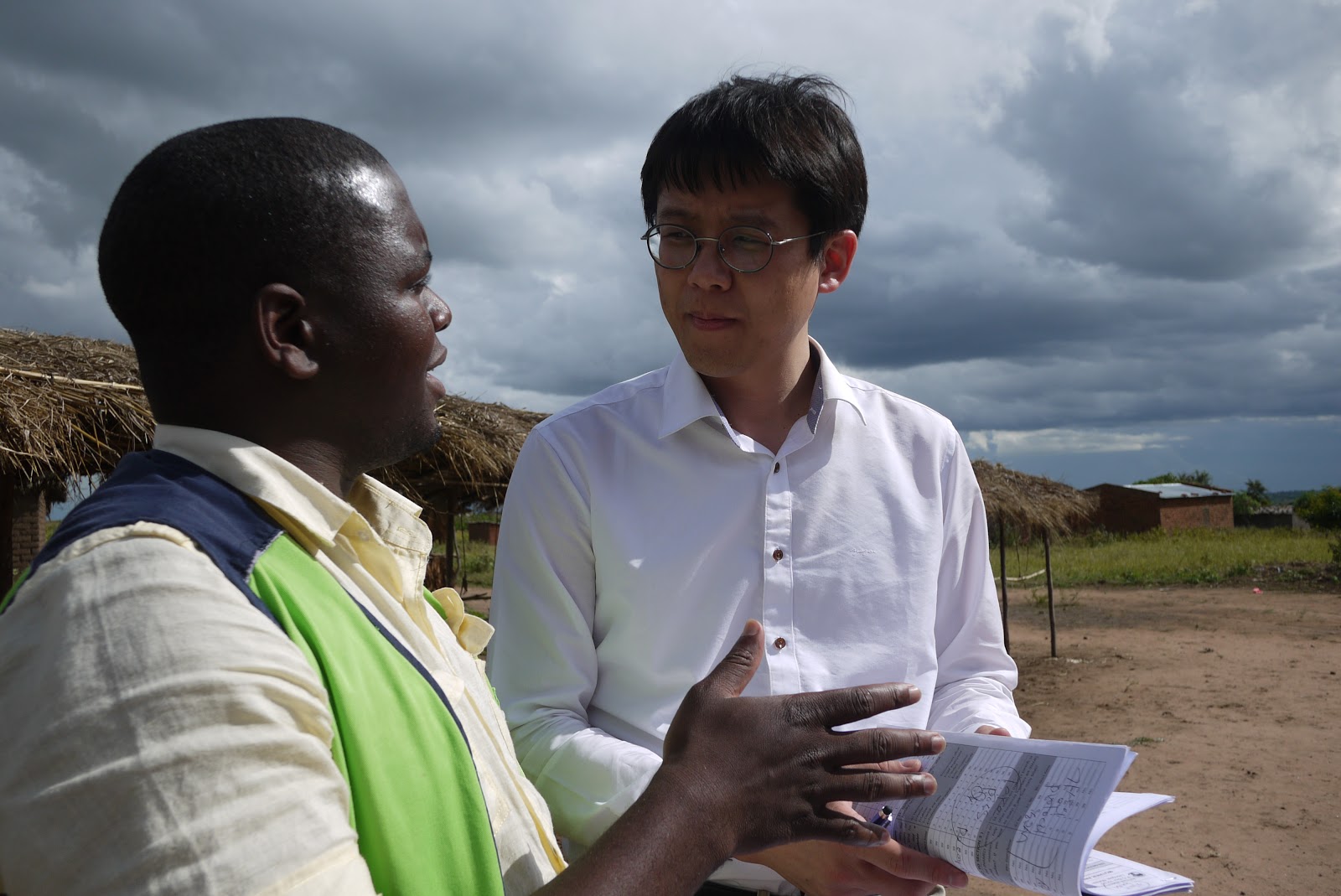

For example, in one paper I published two years ago in Science, we randomly provided tuition money for female secondary school students in Malawi. We then followed these people in the long run. One of our major findings was that the group that received the tuition money showed much better decision making quality, and made much better and much more careful investments. The implications of better economic decisions are huge right? We were able to show how secondary school education improved the quality of life for these women, which as far as I know, is the first causal evidence of secondary school education. Most research in this area focuses on primary school education.

Another approach in my research is to make use of natural experiments and large comprehensive data, which usually means looking at interventions created by the government. To study these effects we need to find a suitable control group. Government policy only affects certain groups of people based on income, residential area, family structure, age, and so on. The key is that most of these policies usually have a cut-off point. For example, if a government introduces a policy based on your income, there will be a group of people just above the cut-off, and a group of people just below the cut-off. These people are super similar, but are treated completely differently, which we can use to our advantage. This is one way we use to estimate the effects of government policy.

Sze Yu Wang: You’ve done a lot of interesting work in Malawi and Ethiopia. How did you first get involved with that, and what inspired you to look at those places in particular?

Professor Kim: Fifteen years ago, I didn’t have any connections in Ethiopia and Malawi. One of my friends randomly invited me: “Bryant Kim can we go to Africa together?” (laughs) I followed him, and we visited Malawi and Ethiopia. The reason he invited me was to visit the hospitals there, and surprisingly, one of the best hospitals in Malawi was actually run by Korean missionaries. They asked me if there was any research I could do in their hospital, and that was how our project started. One study we did was the cash-transfer project for secondary school female students which I mentioned, and another was on the impact of male circumcision on risky sexual behaviour and HIV prevention. These two programs were implemented in Malawi almost 10 years ago, and I still follow up on these people to see how the program affected their lives.

In Ethiopia, we introduced some health and nutrition programs. Unfortunately, we had to stop these projects because of serious political protests in the area. More than 500 people were killed nearby, and one of the American postdocs from U.C. Davis was killed on a road that we often took. It could have been myself, my wife, or anyone on our team. It was too dangerous, and we had to evacuate permanently.

Sze Yu Wang: How do you think the COVID-19 pandemic might disproportionately affect people in lower socio-economic classes?

Professor Kim: Within the US, there is clear evidence that black people and people in lower socioeconomic classes are more likely to be infected by COVID-19. Just look at the incidence and mortality of COVID-19 by level of income, or by residential area—the effects are obvious. But I think that education could have much bigger negative consequences that unequally affect people.

What are the consequences of not coming to school? There is lots of evidence that schooling has important impacts on mortality, longevity, crime rates, and future income. It also affects non-cognitive abilities, because school is basically where you learn to talk to people. People are losing these opportunities. Richer students are able to receive education through other channels, but for poorer students, school is everything. The infection rate of course is unequal, but I think a more serious impact could be driven by an unequal opportunity of education. This must be studied in the future.

Sze Yu Wang: What about people in developing countries?

Professor Kim: Good news! COVID-19 differs by age group. Under 65, the mortality rate is very close to influenza. Influenza infection is tough, but it is very unlikely to kill you. If you are older than 65, however, things change a lot. The mortality rate is almost 10 times more serious. Thanks to the age structure of developing countries, it seems like their mortality rate is much lower than in European countries, where most of the infected are elderly people. Developing countries have worse health-care, which definitely has an impact, but because of their youthful age structure things are not as serious as in Western countries. Look at Ghana: 48,000 cases but only 320 deaths, which is pretty low.

Sze Yu Wang: You started with a degree in medicine, you travelled all over the world, and you’ve worked as an ER doctor, a public health physician, and now an economist. What advice might you have for college students who find that their interests transcend the typical boundaries of their major?

Professor Kim: You guys are 21, 20. Don’t be afraid to explore other areas. When I first studied economics I was 25, which is still young, but older than you guys. I decided to invest at least two years studying economics, even though I didn’t know how capable I was, or even how much I truly liked it. By investing these two years, I learned that this was what I wanted to do.

Take advantage of UC Berkeley’s flexible system for choosing majors and taking courses. Explore yourself! Every summer you have freedom, so explore the world. If I were you guys I would spend one summer as a backpacker. Maybe it’s difficult during COVID-19, but after it is gone, it’s definitely worth a try. I backpacked to Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, which could be dangerous nowadays, but when I was your age the world was a lot safer in terms of terrorism. Take advantage of each summer and study yourself. Find what you like, and what makes you happy. Oh and try to find a girlfriend! Don’t be too shy. (laughs).

Featured Image Source: Professor Kim’s Website

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.