SETH BERTOLUCCI – APRIL 30TH, 2018

There’s no doubt that the global balance of power has shifted east in recent years. The rise of India and China has fundamentally altered the modern world, whether that be politically, economically, demographically, or sociologically. Both nations, with their gigantic populations and extensive resources, now command yet again a level of worldwide influence not seen since the mid-19th century. And the rapid economic successes both achieved in recent history, China since 1978 and India since 1990, have helped to push Asia towards an unprecedented level of prosperity. People like to connect Asia’s massive growth in both productivity and living standards over the past 40 years with vague rhetorical points about globalization or the pending eradication of poverty. But that narrative misses out on the bigger story.

While many like to focus on the similarities between India and China, what’s more important are the differences. Most central to this article is that the two nations rely on entirely different systems of political economy. India is the world’s largest parliamentary democracy, while China is a one-party dictatorship. India’s reforms have scaled back state-run industries, while China’s reforms have created a pseudo-free-market command economy. India has courted the capitalist West while China has tried to counter it. Looking at how China and India have been simultaneously so successful yet maintained their differences can shed light on the “why.”

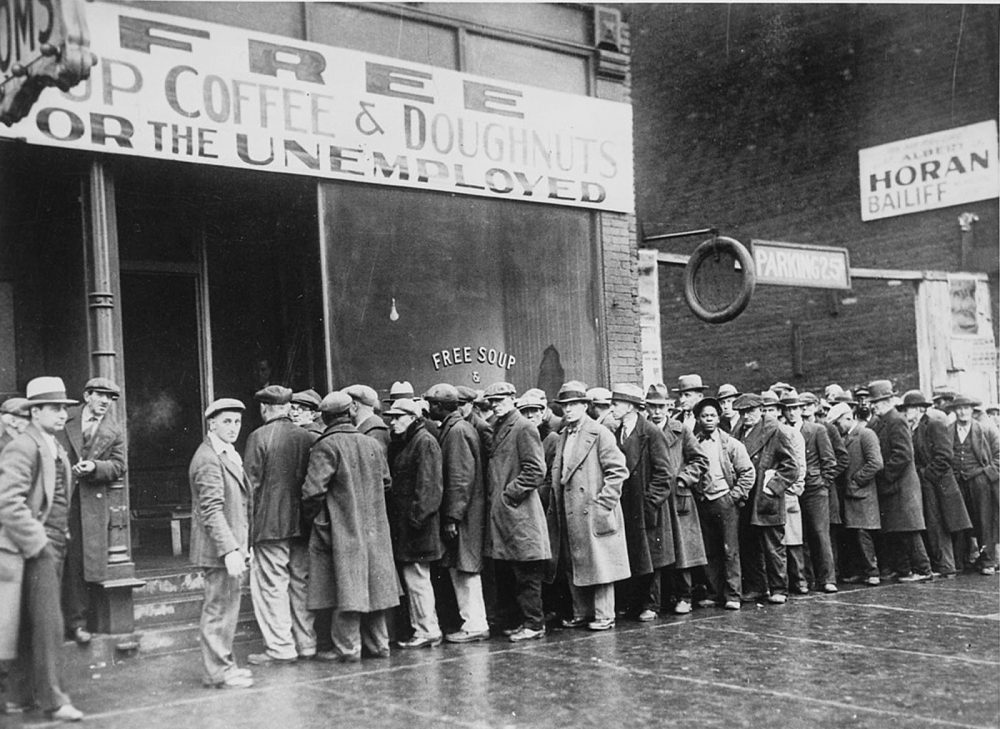

We’ll start with China. Once the Communist Party seized control in 1949 and declared the nation a People’s Republic, China embarked on a campaign of state-led industrialization that failed miserably. Mao Zedong’s most ambitious project was the “Great Leap Forward,” which attempted to develop China even faster than Stalin developed the USSR. The state collectivized agriculture and forced peasants to begin making steel in backyard furnaces. Lasting from 1958 to 1960, the Great Leap Forward led to the deaths of 45 million Chinese, mostly as a result of famine and disease. The “Cultural Revolution” from 1966 to 1976 resulted in huge political purges and a mass exodus of people from cities to the countryside. While countries like Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan all began to approach Western living standards from the 1950’s to the 1970’s, China’s GDP per capita in 1978 was a meager $307 (measured in 2010 dollars). However, 1978 was also the year that Deng Xiaoping took control of the Communist Party and began creating modern China.

Deng and his successors went forward with major reforms. The Communist Party weakened collective agriculture by allowing peasants to leave and farm their own land, and instigated the one-child policy in 1979 to control rapid population growth. While still brutally crushing civilian dissent (most notably the 1989 incident in Tiananmen Square), the Chinese government established “special economic zones” to experiment with market-led policies and permitted the opening of the Shanghai Stock Exchange in 1990. Over the next decade China also took steps to allow greater convertibility of the Yuan, opening up the country to far greater trade. The Middle Kingdom began a $500 billion bank bailout in 1998 to strengthen its financial sector and finally joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. As a result the country opened up to foreign investment and began domestic economic liberalization, further strengthening private enterprise. By 2006, the private economy finally eclipsed the public economy in its share of GDP. Under the leadership of President Xi Jinping since 2012, China has continued its economic ascent.

Yet despite its strides towards economic liberalization, China remains an oppressive one-party dictatorship. Just look at all the state censorship of memes relating Xi Jinping to Winnie the Pooh. At the most recent gathering of China’s National People’s Congress, representatives voted almost unanimously to abolish term limits for the presidency. This move could allow Xi to stay in power indefinitely if he so chooses.

The government still has a very visible hand in the market, too. China’s state-run businesses remain a massive portion of the economy and wield huge power. While there is much concern over China’s corporate debt (clocking in at 165% of GDP), Western commentators often forget that much of that debt can simply be cancelled by the government, especially liabilities owed to domestic financial institutions like state-run banks. Under Xi, a record number of private businesses are revising their corporate charters to allow for a specified role for the Communist Party within their companies. And in 2016, the government even issued a decree banning all architecture deemed “weird.” China has indeed retained much of its command economy.

To call China’s development trajectory purely communist or capitalist would indeed make both Karl Marx and Adam Smith roll over in their graves. Deng Xiaoping and those who followed have ambitiously used market forces when convenient, and cast them aside when not. This mixed system has generated impressive economic successes at a high political cost.

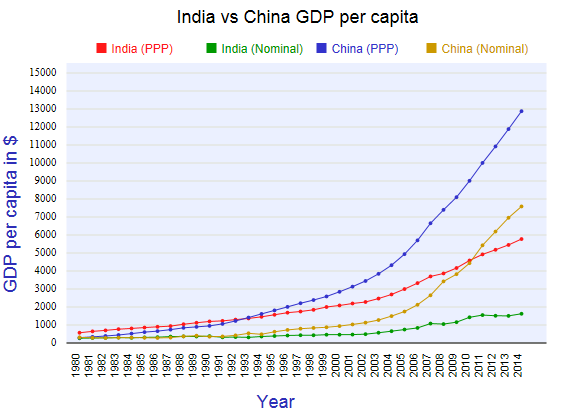

But what about India? As can be seen from the graph, India’s ascent has been far more modest but still significant. Unlike China, India since independence has remained a functional parliamentary democracy. Since the 1990’s the country has pursued more traditionally Western economic reforms that have transformed India into the world’s third largest economy.

Since India’s independence from Britain in 1947, its economic history has largely been a troubled one. The first Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, steadfastly insisted on socialist economic policy. He and his successors created a vast array of highly inefficient state-owned enterprises affecting all major industries, including telecommunications, mining, and transportation. India suffered nothing as terrible as the Great Leap Forward, but its economy grew on average a meager 3.5% annually from the 1950’s to the 1980’s. Indian GDP per capita as a share of American GDP per capita even declined over the period. The government also instituted a currency peg that systematically overvalued the rupee, and exports struggled. Despite continuously peaceful transitions of power (save for “The Emergency” from 1975 to 1977 under Indira Gandhi), India endured significant economic stagnation.

These economic issues all came to a head in 1991. After years of trade deficits, the Central Bank became unable to maintain India’s currency peg to the dollar. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) reached a level low enough to finance merely three weeks of imports. After emergency loans from the International Monetary Fund, India decided to float its currency, which devalued the rupee and increased the competitiveness of Indian exports. Soon after, new elections ushered in prime minister P. V. Narasimha Rao, who pursued significant reforms. Rao weakened barriers to foreign investment, privatized some of the public sector, and reduced the fiscal deficit. Independent of political party, Indian prime ministers since Rao have successfully pushed through further privatization of inefficient state-owned enterprises and opened the country to foreign direct investment. Of a labor force of 520 million, only 1.2 million now still work for state-owned firms.

The Indian economy since 1991 has done well. After the reforms, real GDP per capita is now 3.5 times higher and India has taken the place of the world’s third largest economy measured at purchasing power parity.

As the newest economic superpowers, how are India and China using their power in the international sphere? In foreign affairs, China has been notably assertive. Whether that be engaging in territorial disputes with Vietnam, the Philippines, Japan, and South Korea or sponsoring the One Belt One Road initiative across Eurasia, China appears to be building a profile as an alternative superpower to the capitalist West. While the Chinese continue to pursue trade ties with the world, the nation’s trade policies have led countries like the United States to accuse China of foul play through intellectual property theft or excess steel production.

India, on the other hand, has cozied up to the powers it once proudly ignored. As a key founder of the Non-Aligned Movement in the 1950’s and 60’s, India was instrumental in building a coalition of nations opposed to both American and Soviet influence. But since 1991, India has embraced economic policies that fall into line with standard capitalist policy: they’ve opened up to trade while embarking on deregulation and privatization. New Delhi has become increasingly close to Washington under the Trump administration as Indian leaders fear an ever more powerful China.

Both India and China are developing rapidly, and the world is watching. Although the two nations initially embraced socialist economics in the middle of the 20th century, India and China have very much gone their separate ways. As India moves towards a more traditional free-market system, China embraces a command economy while employing capitalism when convenient. The two countries operate under vastly different political and economic systems, and have vastly different goals internationally. Once India and China eventually become superpowers (if they are not so already), they will likely be more rivals than allies. What effects this will have worldwide remain to be seen. But indeed, the rise of India and China will certainly prove to be the most significant event in the global political economy of the 21st century.

Featured image source: Quartz

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of The Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California at Berkeley in general.

Extraordinarily well crafted review of India’s and China’s economic reemergence .

What an amazing article. Seth Bertolucci, you are a rising economics star!

good job