SZE YU WANG – FEBRUARY 18TH, 2021

EDITOR: PALLAVI MURTHY

In August last year, crowds of maskless partygoers packed into Wuhan Maya Beach Water Park to attend an electronic music festival. During COVID times, such social gatherings have often been branded as selfish and irresponsible. In Wuhan, however, this event was heralded by government officials as a celebration of China’s ‘strategic victory’ over COVID-19.

While the Western world remains in the throes of the pandemic, China has quietly returned to relative economic and everyday normalcy. Live concerts and music festivals mark the culmination of a months-long battle against the virus, in which the Communist Party has ruthlessly employed lockdown regulations, economic policy, and fierce propaganda.

The Wuhan Lockdown

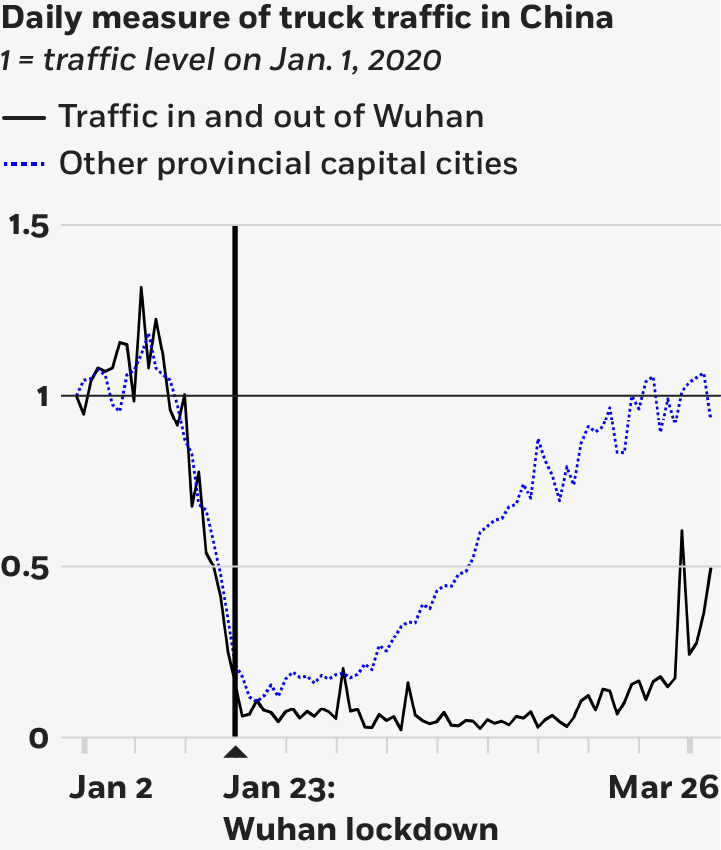

In December 2019, a cluster of mysterious pneumonia-like cases, later to be known as COVID-19, were identified in the city of Wuhan. After an initial cover up by local authorities, the Chinese central government stepped in. On January 23rd, it implemented a 76 day lockdown that closed all non-essential businesses, suspended public transport, prevented citizens from leaving the city, and allowed only one person per household to buy groceries once every three days. Other provinces soon followed suit and announced their own lockdown regulations.

Of course, locking down a city of 11 million inhabitants is not without consequences. An article published in Nature estimated a direct economic loss of 21.6 billion yuan and an indirect loss of 36.4 billion. The suspension of highways and railways crippled the logistics and warehousing industries and heavily damaged Wuhan’s important secondary sector. Industries involved in the manufacture of refined petroleum products and the processing of nuclear fuel suffered the most losses from the disruption of directly affected sectors, such as storage and transportation.

The Spring Festival season, which typically takes place between January 23 and February 22, also coincided with Wuhan’s lockdown. Tertiary industries usually flourish during this time of year, when billions of trips are made around the country on buses, airplanes and railways. However, this year, travel dropped by almost 50% due to strict quarantine and social distancing regulations.

An equally damaging effect was the lockdown’s impact on mental health. As Wuhan hospitals became overwhelmed with cases, both medical staff and patients were placed under psychologically stressful situations. Hospitals lacked protective gear, test kits, and other supplies, meaning doctors often fell sick with the virus while patients were rarely lucky enough to be tested. This enormous pressure exposed China’s underdeveloped and insufficient mental health sector. During the lockdown period, mental health hotlines were inundated with calls from residents who feared catching the virus, or were suffering from general anxiety and depression. A survey conducted by psychology experts on front-line medical workers found that between 33 and 39 percent of respondents had experienced anxiety, depression, somatic symptom disorder, or other problems. The total economic loss from mental health issues was estimated to be approximately 115 billion yuan. By the time the lockdown finally ended on April 8, the central government was faced with both a tanking economy, and a psychologically scarred workforce.

Controlling the National Narrative

In other parts of the world, governments have faced public criticism for their virus containment policies. Protests for and against COVID regulations have surfaced across Europe, while in Hong Kong and Thailand, handling of the pandemic has fueled pre-existing public unrest. A crucial part of China’s economic recovery was the government’s ability to maintain political control by manipulating the public narrative and squashing dissidence.

First, Chinese state media pinned the blame for the initial bungled response on local government officials, many of whom were forced to resign. In contrast, central government leaders were portrayed as saviors of the Chinese people, and criticism of their actions was suppressed through tightened censorship. A Canadian research team found that, between January 1 and February 15, at least 516 coronavirus-related keyword combinations were blocked on WeChat, including references to President Xi Jinping, discussions of government policies, and calls for collective action.

The Chinese government also took advantage of nationalistic spirit by painting Wuhan doctors as patriotic heroes. On February 7, Dr. Li Wenliang died of COVID-19 in Wuhan Central Hospital—in late December, Dr. Li had attempted to share information about a worrying new illness (COVID-19), only to be silenced by Wuhan authorities. As news of his death spread, the government capitalized on public outrage by bestowing him the title of ‘martyr,’ the highest honor the Communist Party can give a citizen killed working to serve the country. A potential embarrassment of government failure was transformed into a symbol of proud Chinese spirit.

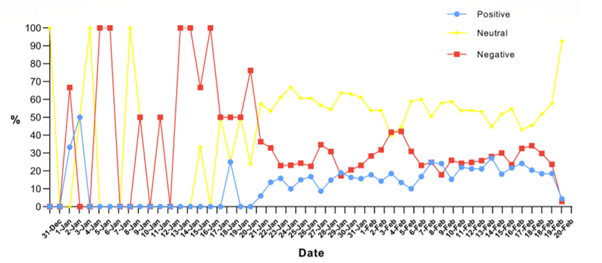

The Communist Party strongly believes that the key to economic growth is political and social stability. In this respect, their fierce censorship and propaganda have proved effective in consolidating public opinion and thus setting the stage for economic recovery. A paper published in the Journal of Medical Internet Research analyzed the sentiment trend of hot search topics in China. From mid-January to early-February the overall sentiment had shifted from mostly negative to mostly neutral.

An Uneven Road to Recovery

As new COVID-19 cases have subsided, the government has gradually reopened factories, shops, and offices, while keeping the virus at bay by maintaining strict restrictions on foreign visitors. China became the only major economy to grow in 2020, expanding by 2.3%.

In May, the Chinese government launched a 3.6 trillion-yuan fiscal stimulus package. Rather than focusing on consumers and households, the package was investment-oriented, aimed at boosting spending on infrastructure. Chinese GDP growth contracted 6.8% in the first quarter, but has since rebounded to 3.2% in the second quarter and 4.8% in the third quarter. Amidst a global pandemic and trade tensions with the US, Chinese exports have also recovered and grew 9.9% on the year in September. This is in large part thanks to Chinese producers diversifying their supply chains in response to the trade war and pivoting to Taiwan and Vietnam, countries that have both managed COVID-19 relatively well.

The service sector has recovered the slowest, with household consumption showing only marginal improvements in the second quarter. However, in contrast to the lost tourism dollars from the Spring Festival travel rush, this year’s Golden Week holiday demonstrated an impressive recovery only six month’s removed from the lockdown. During the 8-day public holiday, more than 637 million people travelled within China, generating 466 billion yuan in revenue. High speed railway tickets were sold out within hours, and popular tourist attractions were packed with crowds of sightseers.

However, despite positive signs from most macroeconomic indicators, concerns that the pandemic will have lasting effects on economic inequality have cast doubt on China’s success story. Most of the growth has been concentrated in wealthy coastal regions, such as Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangdong, while provinces in landlocked parts of the country have recovered far slower. China Beige Book’s survey of over 3,300 firms found that businesses in most interior provinces saw declines in production, revenue, and profits in the third quarter, leading some to question the validity of China’s official GDP figures. In addition, slow progress in strengthening social safety nets, combined with the investment-oriented focus of the fiscal stimulus, has left lower-income citizens worse off. Recent increases in high-end consumer spending have not been accompanied by a similar recovery in low-end consumer spending. In the long run, China’s approach of boosting growth by building bridges and railways can only go so far if its millions of unemployed are still receiving no income and minimal social benefits.

Damaged International Credibility

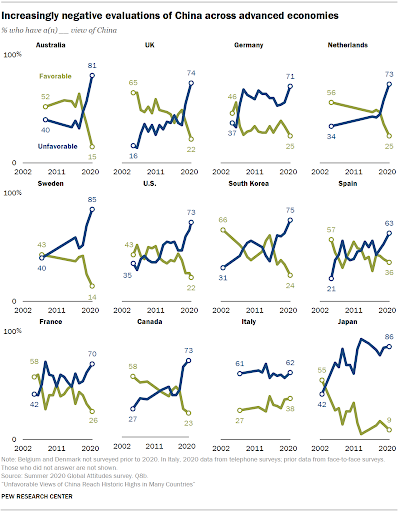

China’s virus containment strategies and state media narrative may have allowed for a relatively stable return to economic normalcy, but they have also negatively affected its international image. The government’s untransparent conduct in the early days of the outbreak left a lasting memory in the minds of governments across the world, while as worldwide cases continue to grow, politicians have also questioned the accuracy of China’s reported case numbers. Up until late March, the Chinese government had ignored WHO regulations by not including asymptomatic cases in its total case count, further contributing to international mistrust.

To divert public attention from the failings of the government, the Communist Party’s national narrative involved cracking down on human rights in Hong Kong and Xinjiang domestically, while engaging in aggressive foreign policy abroad. In March, Chinese foreign spokesman Zhao Lijian tweeted, “It might be the US army who brought the epidemic to Wuhan” and “Be transparent! Show us your data! The US owes us an explanation!” A month later, the French foreign office was forced to summon the Chinese ambassador after Chinese diplomats that claimed that France had left its elderly patients to die. Although these provocative moves may have soothed internal unrest, the result has been a decline in public perceptions of China among most developed countries.

This erosion of international trust arrives at a critical juncture in China’s economic relationships with Europe. In July, the United Kingdom decided to ban Huawei from its 5G networks—a decision that was likely influenced by China’s COVID cover-up as well as its hostile response to international criticism. China’s relations with the EU also suffered, and trade talks on the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) grinded to a halt in mid-2020 (though the two sides eventually reached an agreement in late December). Europe is emerging as an important battleground for the US and China in their fight for global leadership in trade and advanced technologies, and this recent trend of anti-China sentiment will certainly do the Communist Party no favors.

China’s method of containing the virus through draconian lockdowns and emphasizing nationalism and political stability brought short-term economic rewards. It has put China in a better position than any other developed economy in the world. China now hopes to restore its international image by racing to distribute its COVID-19 vaccine. Only time, however, will reveal the economic effects of its imbalanced recovery, its damaged reputation, and the potential public anger that might continue to ferment under the lid of censorship and suppression.

Featured Image Source: South China Morning Post

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.