NICOLAS DUSSAUX – MARCH 2ND, 2020

EDITOR: PEDRO DE MARCOS

Recent political debates in the United States demonstrate the concern of the American population about the possibility that the United States will leave the club of liberal – or free – market economies and instead embrace socialism. ”America will never be a socialist country” declared Donald Trump during a rally in Wisconsin, when he kicked off his reelection campaign. While some pundits consider that socialism is making a return in the United States, there is evidence that the country is still very far from becoming a socialist country. Nevertheless, the rhetoric of candidates like Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren on economic matters are underlining the idea that half of young Americans are questioning the way the American economy is structured.

Propositions like increasing taxes on the stock exchanges to finance student debt, providing Medicare for all, redefining US trade policy towards a more ecological agenda, and increasing the share of worker’s ownership of big corporations conflict with what the United States have represented for decades. Given the popularity of these measures, is this the time to bet against capitalism and predict its end? Probably not, and this political disruption is maybe the first event of a slow shift from a liberal market economy to a more regulated and state-controlled system. Of course, socialism has many definitions, but it cannot simply be defined as a more responsible and fair economic system as some of its proponents would describe it.

In “The Road to Serfdom,” the Austrian economist, Friedrich Hayek, described most European economies – where the state coordinated a war economy – as socialist countries. We cannot use this definition either. To clearly understand our approach, we are going to characterize socialism as a system in which the means of production are shared, whether through a state-ownership (which had been partly the case in the Soviet Union and in China) or through collective ownership by a group of workers.

This definition is very far away from what America is. However, it is no longer possible to ignore the fact that all over the world, most developed economies seem to have resolved some of the most prominent problems of America without shifting to a socialist model. We propose in this article to break down the concept of capitalism thanks to a typology developed to analyze the varieties of capitalism.

If we want to compare the American capitalism to other systems in the world, it is necessary to have a criterion that could be evaluated in every country we study. In their seminal book “Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional foundations of comparative advantage”, Hall and Soskice propose to use the private firm as the principal way to compare economic systems. Indeed, the analysis of capitalism revolves around the interactions the private firm has with the state as a regulatory entity. In several fields such as the execution of contracts, the regulation of the labor force, corporate taxes, imports and exports, the relation between these two agents play a great role. As we defined it earlier, one of the main characteristics of socialist systems is the predominant place of state-ownership. Controlling companies is a way for the state to operate a business in a logic that differs from the capitalistic one, that we understand as the maximization of profit. Once the stakeholders of the company abandon this logic, it expands the possibilities of the company. For example it can serve public good, operate a monopoly without making the consumer pay an unreasonable toll, contracting with public entities such as the army without any risk of strategic information leaking or hostile takeover. Indeed, a non-state owned company is held accountable by its shareholders, while a state-owned one is providing a public service. Moreover, the government can be held accountable for the activities of state-owned companies, which might make the services they perform politically motivated. The recent example of the catastrophic management of the energy infrastructure in California by Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) reignited the public debate for more public ownership and regulations of monopolies in America.

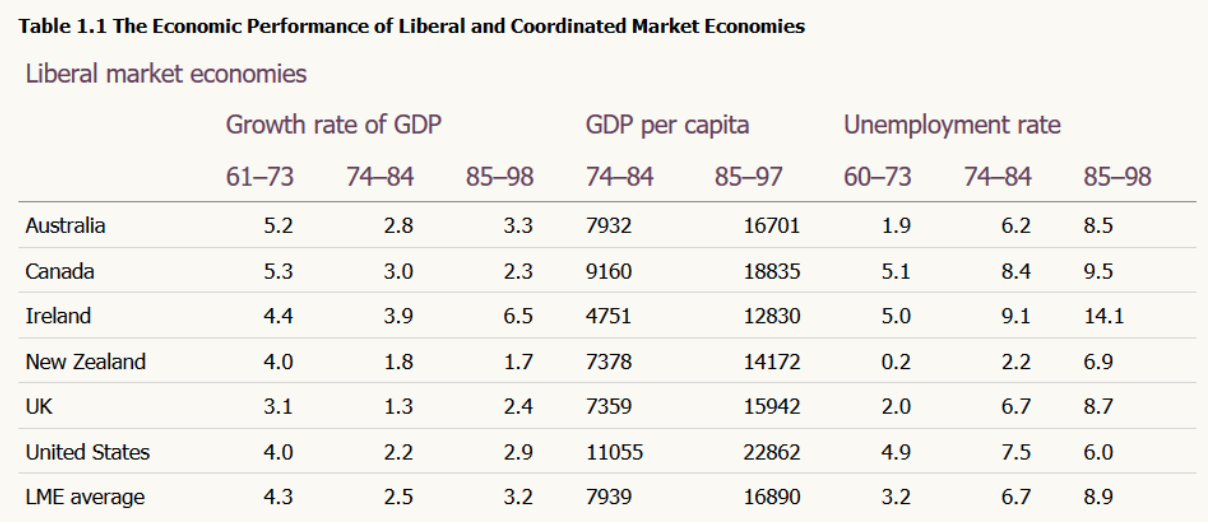

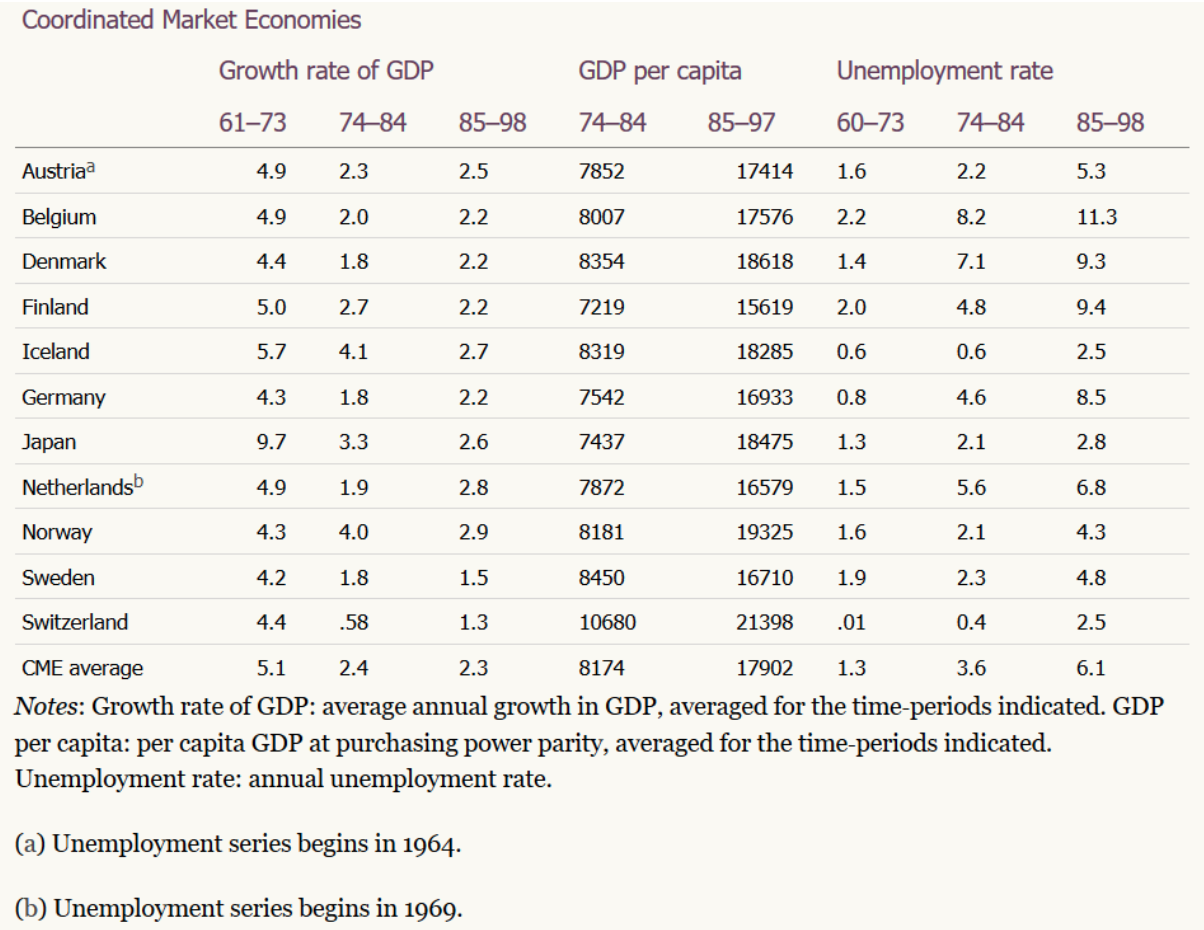

But what we want to point out here is that despite the political discourses of the candidates at the DNC primary, America is highly unlikely to become a socialist country and will most probably move – in case of a Democrat victory at the next presidential election – towards a more heavily regulated capitalism. The general distinction is made between liberal market economies (LMEs) and coordinated market economies (CMEs). We generally classify the Anglo-American model as an LME and the diverse European models in the CMEs, given the fact that the state emerged in Europe as a general coordinator of the economic system in the wake of the 50’s. The LMEs are characterized by little government intervention in the general economic organization and by the importance of the market in the production choices. The CMEs are economic systems that obey different logic when it comes to coordinate the production, with a heavier role for the state as an economic strategist. Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to believe that these classifications are inflexible . We assist since the 1990’s to a phenomenon of “Americanization” of the world economies. This expansion of American values is mainly realized through multinational corporations that alternatively export the values of their home country abroad and import some of their subsidiaries at home. It is still important to note that these exchanges are often “creolizations” and that they do not happen without important modifications. The two main models for CMEs are France and Germany, which are characterized by a heavy role of the state in the economic system, a feature inherited from the reconstruction period they endured after the two world wars.

Of course, there is also public ownership and a presence of the state in the national coordination within the LMEs. Only in the United States, two thousand state-owned entities are distributing a quarter of the nation’s electricity. Most of the public transportation infrastructures and airports are also publicly held. This is not sufficient to qualify the United States as a CME, for the reason that there is a consensus that some companies are inherently meant to be publicly held, because of huge fixed costs (cable, highways) or because they are not profitable but still socially desirable (public transportation). Such is the case of Amtrack, the public transportation company that although is not profitable, it is operated by the state because it represents a social benefit. To stay afloat, Amtrack uses financial equalization, a system that consists in compensating the operating loss in the least profitable lines by a higher toll on the profitable lines. The reason for that is that the state-owned companies are obeying to a non-market logic: here, the goal is to allow equal accessibility to the American territory, not only in the most profitable areas. Equally, most public infrastructures (like swimming pools, public parks, etc…) are public because they are the result of an effort of the state to elicit the willingness to pay of the citizens for some infrastructure that would not exist otherwise.

The frontier between CMEs and LMEs is blurred, but the frontier between capitalism and socialism is tangible. With the exception of North Korea, there are no socialist powers anymore. Scholars start to turn towards the study of new types of capitalism such as the Chinese “state-capitalism”, a new form of market economy in which the private property is an equivocal notion and where the government uses executive power to coerce economic activity rather than incentivizing businesses.

In the American case, the debate is less centered on the dichotomy between capitalism and socialism than between liberal market economies and coordinated market economies. The most common point between policymakers throughout history is their concern with questions of efficiency. A recurring subject in the political discourse is that the United States should draw lessons from the successes of public ownerships in other countries. For instance, within the OECD, the fully nationalized healthcare system (NHS) of the United Kingdom seems to stand out. Equally, the French public education allows the French people to avoid the huge burden that is student debt. Nationalizing PG&E could be for the California state government far more efficient than bailing it out. However, even public ownership has its limits and these models are not exempt from problems. The public health system in the UK has been struggling for decades, as it revealed itself being unable to handle the demographic changes of the British population. Underfunded and unable to adapt itself to the evolution of the demand of care, the NHS raises questions on its sustainability. The French public universities are underfunded as well, and the last ten years saw the phenomenon of “brain drain” skyrocket in France. Only in the field of economics, well-known searchers such as Gabriel Zucman, Emmanuel Saez and Esther Duflo are now conducting their research in the United States. Trying to draw lessons from these relative successes would be difficult for the United States, if not impossible.

Source of the table: Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage

Moreover, the data shows us that LMEs have seen in the past higher growth rates of their GDPs and lower unemployment, which led some developing countries to adopt deregulation laws directly inspired from LMEs. “It does not matter whether the cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice.” This famous sentence was pronounced by Deng Xiaoping, former leader of the Chinese Communist Party. When he consolidated his power in the early 1980s, he started to open China to foreign investments and imported selected parts of the capitalist systems. This new system, named state-capitalism by the scholars, has allowed China to develop very rapidly since then, with their GDP growing by approximately 10% each year. Selecting what works abroad, reproducing it and improving the overall economic model of our countries seems like a simple and pragmatic plan. Unfortunately, as Marie Shirley shows, basing reforms on econometric measures between countries is a process very unlikely to work. Given the crucial interdependencies between the economic structure of a country and its political culture, policymakers have a reduced panoply of choices for structural reforms, the width of which depends on its political ability to implement change. To understand the two classifications, it is also important to know the historical reasons for such differences between countries that belong to the ‘free world’. In this matter, the philosopher Karl Marx provided in his young years an historical analysis on the formation of the state and its relations with the private sector. Marx considered that “the economic structure of the society is the concrete basis on which is built a political and social superstructure”, which suggests that the political form of the state is very dependent on the pre-existing economic conditions. In American history, the bourgeoisie was always tied with the government. Conversely, in Germany and other European countries that experienced feudalism, the state rose as a competitor of smaller economic agents, such as commercial cities and local lords. This antagonist role of the state paved the way to the development of a coordinated economy since then.

This kind of economic history provides a good theoretical framework to understand where lies the difficulty when it comes to implementing reform. Indeed, the rising “socialist” American movement does not seem to be dominated by low-income workers as it could have been in the past, and some of the poorest workers in the United States view Donald Trump as the guardian of American liberal capitalism. However, Trump’s administration policies are not always as “laissez-faire” as his supporters would want. Big subsidies to the agricultural sector, aggressive trade policies towards China and withdrawal of the Trans-Pacific Trade Agreement constitutes some of the ways America catches its own mice.

Featured Image Source: The American Prospect

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.