KATHERINE BLESIE – MARCH 12TH, 2019

A recent tweet about Jeff Bezos and the astounding magnitude of his fortune is making the rounds on social media. Originally posted by Matthew Chapman, a reporter for the left-leaning online news publication AlterNet, the tweet reads: “By my calculations, as of 2018, Jeff Bezos has enough money to literally buy every single homeless person in America a new house at median market price, and still have $19.2 billion left over.”

In a sense, Chapman is right: if Jeff Bezos had all of his billions sitting as piles of cash in a bank vault somewhere, he could afford to buy a house (at the median market price of $225,300) for every single one of the 554,000 homeless people in the United States. And still have billions left over. But of course, Bezos’ money isn’t sitting in a vault somewhere—it’s tied up in shares of his multi-billion-dollar enterprise. While suggesting that the richest man in the world buy homes for half a million people is clearly not a legitimate policy suggestion, Chapman is getting at an important point: Bezos owns an unprecedented share of the nation’s wealth. It takes him just nine seconds to make what Amazon’s median worker does in a year. Spending $88,0000 is to him what spending $1 is to the average American.

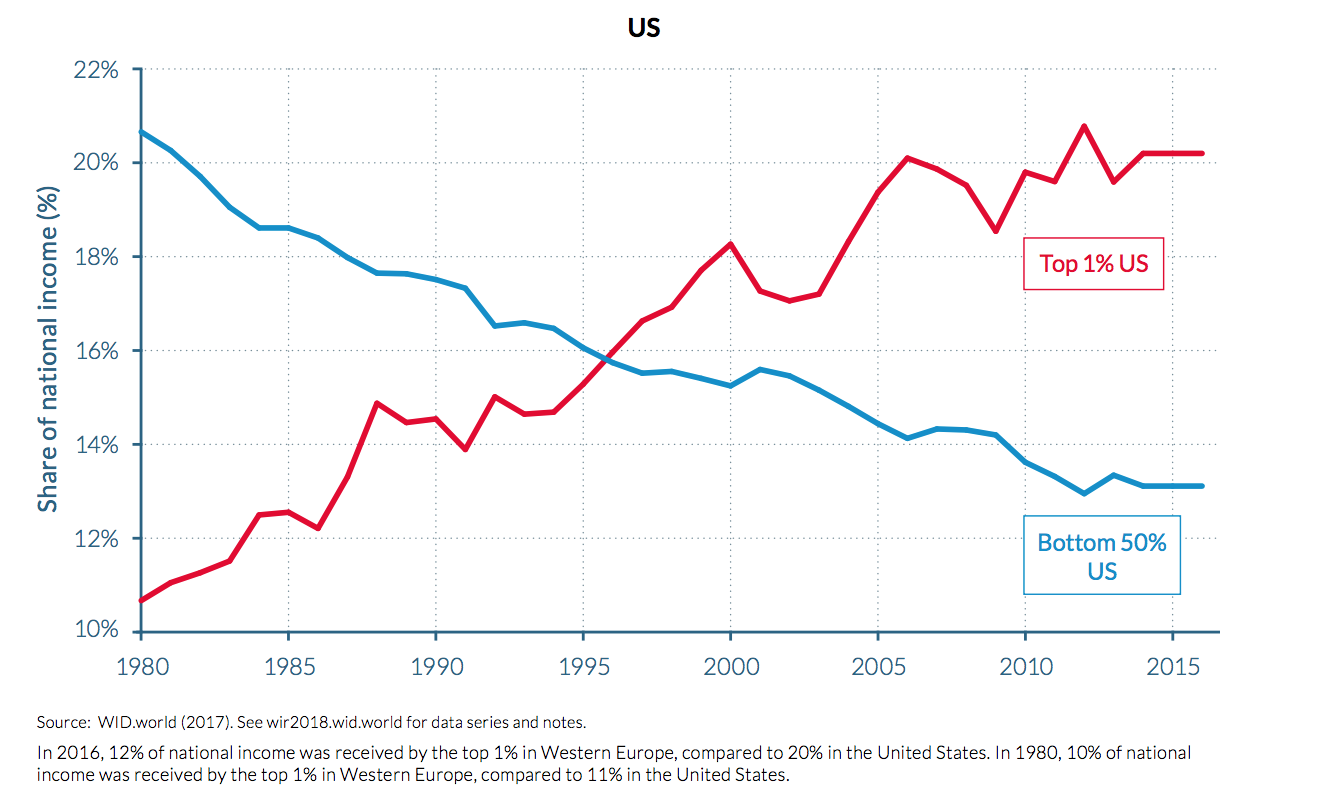

Beyond the extreme wealth concentration among people like Bezos and others in the Fortune 500, top income shares in the United States have reached unexampled levels over the past decade. In 2016, the top 10% of the income distribution in the US was making almost half of the nation’s entire income (47%). In other words, the average income in in the top 10% of our country is 4.7 times larger than the average income in the economy at large. The divergence only increases as you move up the income distribution: the top 1% of American adults makes 20.2% of national income, while the entire bottom half of the distribution, a group 50 times more populous, makes only 12.5% of the nation’s income. Looking at the changes in shares of national income over the past 40 years in the United States reveals very different trajectories for the bottom 50% and the top 1%. Since 1980, the bottom 50% share of income has fallen from over 20% to less than 14%, while the top 1% share has grown from just over 10% to more than 20% of national income. Trends also reflect a divergence in income growth rates between the very wealthy and the middle class. While since 1980 pre-tax income has grown by 61%, for the bottom 50% it has grown by only 1% and for the top 10% has grown by 121%.

Many left-wing politicians are advocating for serious tax reforms to address this growing divergence. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) has recently received a lot of attention for her proposal to drastically increase the top marginal income tax. Specifically, that those making more than $10 million should see their marginal tax rates raised from the current 37% to as high as 70%. Unsurprisingly, conservative backlash has ensued. House Minority Whip Steve Scalise wrote in a January tweet that Ocasio-Cortez’s proposed tax hike was a ploy to “take away 70 percent of your income and give it to leftist fantasy programs.” Tax activist Grover Norquist compared the tax to indentured servitude. Ocasio-Cortez has replied that these criticisms seem to ignore the fact that the high rate of 70% would be a marginal rate, not an effective one: “That doesn’t mean all $10 million are taxed at an extremely high rate. But it means that as you climb up this ladder, you should be contributing more.” A more nuanced response from James Pethokoukis of The Week questioned whether a 70% marginal tax rate on top incomes might dissuade taxpayers from making high-risk, high-reward career decisions that in the past have spurred on economic growth. Another valid concern about extremely high tax rates is that they might put the United States at a huge disadvantage to competitors in countries with lower rates. This is why the EU countries try to have a common tax policy where possible: to avoid a race to the bottom. For the US to move to 70% while its competitors keep their current rates might wipe out export industries.

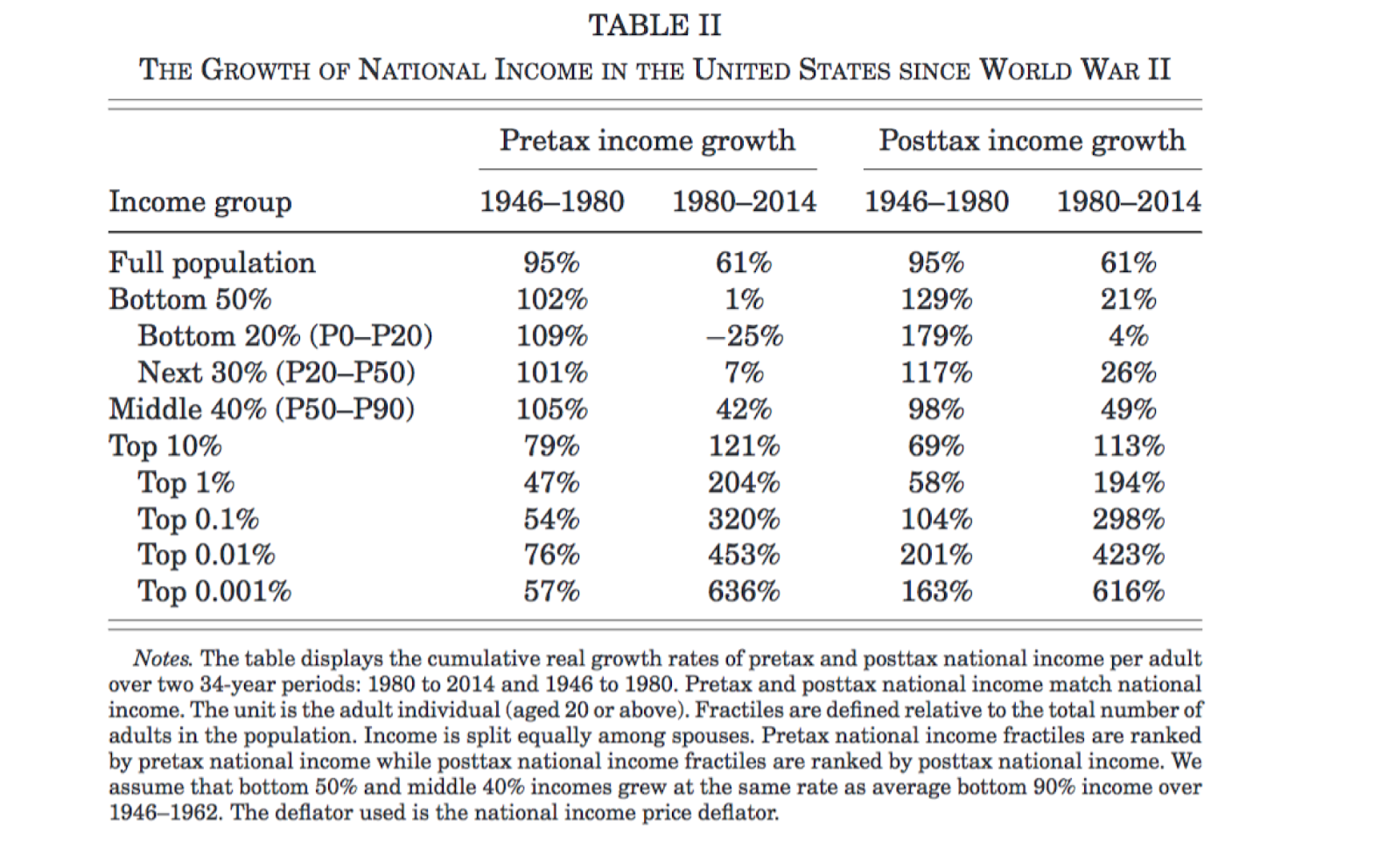

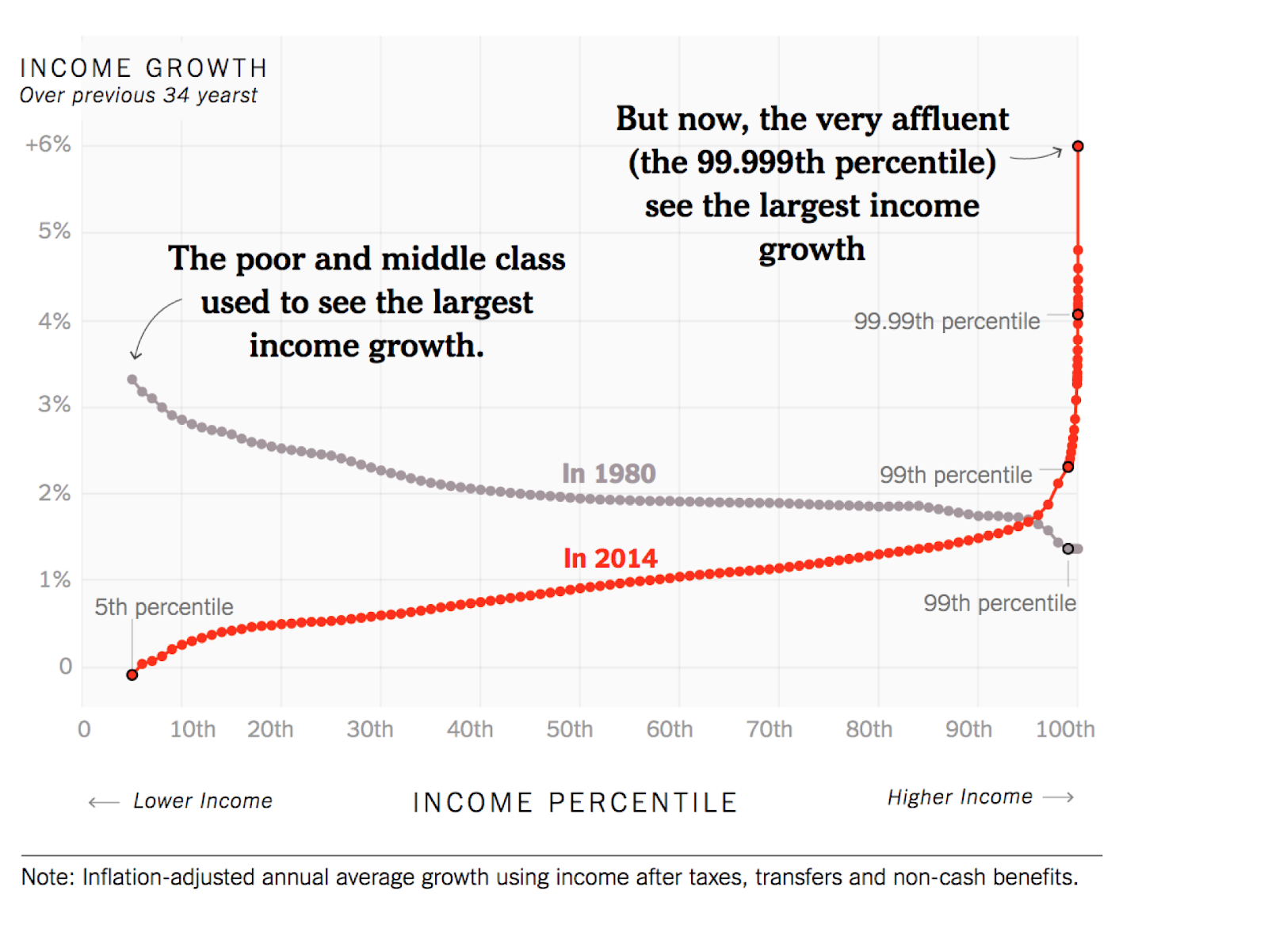

Consequently, the moral landscape of this debate deserves exploring: can the best thing for a society built on the foundation of a free market really be for the government to take more than half of a citizen’s income in taxes, even in a marginal tax rate system? Economists such as Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman argue that yes, it can be. A look back at tax and income data from the past century suggests that our economy, and economies the world over, experienced their strongest periods of growth when taxes on the top of the income distribution were high. Between 1946 and 1980, years when the top marginal income tax rate ranged from 91% to 70%, the US economy experienced stronger and more equitable growth than it has in any period since. From 1946 to 1980, real per capita GDP growth was consistently strong (+95%). What is more, the bottom 90% grew faster than the top 10%. The bottom end of the distribution experienced strong income growth: the bottom quintile grew 179% and the next 30% grew 117%.

Starting in 1980, however, President Reagan made huge cuts to the top marginal income tax rate, first down from 70% to 50% in 1982, and then again to below 40%. Economic growth in the US during this period began to slow, and both income shares and income growth rates began to diverge drastically going up the income distribution. Aggregate growth slowed to 61%, and income stagnated for the bottom 50% of earners at $16,000 per year (increasing by only $200 over a 34 year period). Things were quite different for the top of the distribution. Between 1980 and 2014, income has more than doubled for the top 10%, and tripled for the top 1%. And for the top 0.001%? Income has increased by 636%.

It is helpful, too, to consider growth trends in other countries that have employed similarly-high top marginal income tax rates. When the US occupied Japan post World War II, they imposed a top marginal tax rate of 85%, mainly to prevent the formation of a new oligarchy. From 1950 to 1982, the years that the tax was imposed, Japan’s economy grew 5.1% a year per adult on average, one of the fastest rates of economic growth ever recorded. Top incomes in Japan today reflect the effects of a consistently high top income tax rate. Japan, despite being the third largest economy in the world (following only the United States and China), sees its top 1% earners earning a fraction of what US top earners make. In 2012, the top one percent of households in the US were making $1,264, 065, on average, while in Japan the top 1% made $240,000.

At the other end of the tax rate spectrum lies Russia. In 1991, Russia was faced with trying to piece together a broken economy with new free market ideals. The transition away from a socialist economy was a “shock-therapy” of privatization and price liberalization that happened at break-neck speed. A top tax rate of 30%, modeled on the US’ top tax rate at the time, was implemented. In 2001, that rate fell to just 13%. The swiftness of this transition, including the shockingly low tax rates for the top deciles of the income distribution, led to the creation of a new oligarchy and inequality levels somewhat higher than those observed during the tsarist period.

There are, of course, explanations other than the high marginal tax rate for why the US experienced such high growth between 1946 and 1980. The extraordinary growth of OECD countries post-WWII took place when there was a huge demand-side stimulus in the form of rebuilding Europe. Because Europe’s industrial base was largely destroyed by the war and there were few industrialized countries outside the US and Europe, the US economy took off like a rocket helping Europe re-build. This took between twenty and thirty years, and coincides with the years when the US imposed an extremely high marginal income tax rate. This high-growth period also took place when tariff barriers were high, so the cheap labor of the developing world wasn’t a threat to the high-pay industrial jobs in the west. And, of course, there is the story of automation: it was rudimentary during the aforementioned high-growth period (1946-1980), but it is now ubiquitous and expanding, replacing “low skill” jobs first, working its way up the skill ladder, increasing inequality as it goes.

The high-tax model can work and has worked in some specialized cases, most notably in Norway, Denmark, and Sweden. Some would argue that high taxes have worked in these countries because they are what political economist Francis Fukayama calls “high trust societies”, or countries that display a high degree of mutual trust not imposed by legal regulation. Yet, recent data shows that even in these countries, tax evasion rises sharply with wealth, specifically that the top 0.01% of the wealth distribution in Scandinavia evades about 30% of its personal income and wealth taxes. This brings us to one of the most common critiques of extremely progressive tax systems: won’t higher taxes increase the incidence of tax avoidance and tax evasion? Gabriel Zucman, Assistant Professor of Economics at UC Berkeley, says that this doesn’t necessarily have to be the case: “Too many people have the view that tax avoidance is an unavoidable given, and that if taxes are higher people will avoid or evade more. That’s not true. That’s not what the data shows. Tax avoidance and tax evasion are things that government policy can reduce. If you have a tax system that has few or no loopholes, then you cannot avoid taxes.” A higher marginal income tax need not go hand in hand with tax avoidance, if combined with increased efforts by the government to regulate tax evasion and close legal loopholes that enable tax fraud.

Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez proposes a large marginal tax increase on top incomes to curb the increasing inequality in the United States. While a comprehensive policy plan to curtail inequality must consider more than just progressive taxation and higher tax rates would have to be implemented in conjunction with tighter regulation of tax compliance, data from the past half-century suggests it may be a good place to start.

Featured Image Source: The Daily Star

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.