NICOLAS DUSSAUX – APRIL 1ST, 2021

EDITOR: SEBASTIAN MARSHALL

“There is nothing more useful than water: but it will purchase scarce any thing; scarce any thing can be had in exchange for it.” These words, from the famous economist Adam Smith, sound like a grim prediction as we walk into the 21st century. A number of crucial goods and materials, on which the American economy relies heavily, are becoming scarce by the day, and may well become increasingly expensive. The list is long, and includes rare metals, raw earth materials, sand, and other natural resources that our industrial processes consume in large quantities. Water is one of them, and it might not be because the resource disappears, but because the US infrastructure system is not up to the task anymore.

While California has been grappling with the issue of water scarcity since it developed intensive farming during the exploration of the West, other areas in the US have always had access to reliable water resources. Such communities were part of the collective national building effort during the 20th century. Between the end of the Second World War and the 80s, the number of water public infrastructure projects shot up, based on a model of constant economic development and ever growing population. This assumption was stated clearly by Gilbert White, the director of the President’s Water Resource Policy Commission, tasked with elaborating a water policy for Americans in 1950. If this assumption still held true, this would strengthen the case for continuing to build large and resilient infrastructure systems as was the case in the largest cities in the US at that time. However, despite the fact that the population of the United States keeps growing, the distribution of the population drastically changed in recent years. Researchers from Duke University showed that between the 50s and today, populations massively moved. Different regions were affected differently; large cities where middle-class populations lived chose to move to suburban areas, emptying city centers. The direct consequence of this decrease in the population of city centers was a concentration of the financial burden of infrastructure maintenance, on the generally well less off population that stayed.

In face of this problem, water utilities had no other choice than to raise water bills, making their customers bear the brunt of the problem. The increase in rates was not enough to compensate for the lost revenue, leading to a degradation of the quality of service, provoking a number of events referred to as “utilities disasters.” The most well-known of those was the Flint disaster, a lead contamination that lasted almost five years and provoked nation-wide outrage.

Besides utility disasters, the US still has high levels of non-revenue water, water that is not billed to customers because it is lost in the network, mostly because of pipe breakages. The American Society of Civil Engineers estimates non-revenue water to amount to six billion gallons per day. The EPA estimates this number to be approximately 16% of the total treated water across utilities. This loss in production efficiency is sector-specific but should raise a question: can our utilities afford to lose so much of their output? The answer is no, especially when the cost is borne by less well-off populations. The disproportionate impact on disadvantaged populations prompted the need for a reflection on water equity and on the economic nature of water. Although it is referred to by the OECD as an economic good, developed countries tend to consider water as a public good, and in some cases, a right. From an economic standpoint, water treatment and distribution infrastructure can be understood as a merit good. This concept, introduced by economist Robert Musgrave, characterizes goods for which free-market conditions will lead to a consumption lower than the optimal social amount. Such an outcome generally arises from ignorance on the consumer’s end, or from a misestimation of the value of the good. Namely, the positive externalities and spill-over effects of effective water infrastructure tend to be under-estimated. The tendency to take infrastructure for granted, and to leave large public expenditures to the next administration, led a number of water systems to wear out over time. The gap between available financing and actual utilities investment has been widening over the years, and the American Water Works Association estimates that a $1 trillion in investment will be needed over the next 25 years to maintain the current levels of service.

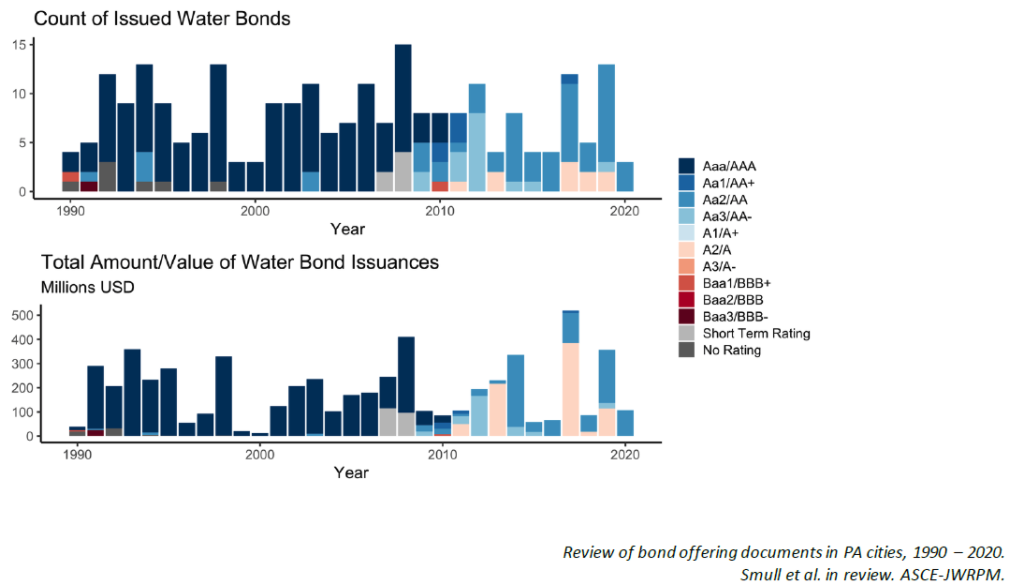

There is therefore a need to find new financing mechanisms that would allow utilities to rely less on the rates they charge their customers. Moreover, as a graduate student at Duke University recently outlined, it has become increasingly difficult for utilities to borrow the funds necessary to fund these capital development projects and refurbishment. Indeed, a study of the grades attributed by Standard and Poor’s to the bonds emitted by local governments of 25 cities in Pennsylvania, showed that the trust of investors in the ability of utilities to refund the loans gradually has declined from 1990 to 2020. This degradation of trust is doubly bad news for utility companies: it makes the financing harder to find, and significantly raises the interest rates on the capital borrowed. This in turn forces an increase in water service rates.

Image source: National Academies

Like the suburban flight, this situation puts low-income households under financial strain, who saw an inflation adjusted yearly increase of 5% in utility rates, compounding to make the burden heavier each year. In North Carolina, one of the four states where the research team of Duke University concentrated their efforts, households making the minimum wage have to work the equivalent of 4 days per month to just afford their water bill.

This situation is hardly sustainable and calls for more radical intervention of the Federal government. One way to solve this problem would be to take action to foster population growth and reinvest these areas. Such ideas are championed by Matthew Yglesias, the founder of Vox, in his book One Billion Americans: The Case for Thinking Bigger. Indeed, a rejuvenated and more dynamic American economy, supported by a larger population, would certainly allow utilities to support the costs of both expanding infrastructure and fixing the existing problems. However, triggering population growth is neither easy nor without consequence and is not merely an economic decision. Some cities had foresight and anticipated the shrinking of their populations, therefore carried out capital reduction projects to alleviate the operations and maintenance costs of their water grid and their sewer systems.

Another way to increase the resilience of the American water grid could be to bet on technological progress, and more importantly, on a shift in the paradigm of water treatment and distribution. For some smaller and remote communities, decentralized water treatment is recognized as a more relevant and efficient solution than large-scale, hardly adaptable concrete structures that can handle humongous inflows and outflows. These decentralized, sometimes mobile, solutions are relevant in both water and wastewater treatment, and alleviate the strain on sewers in case of huge stormwater inflows. These extreme weather events, that are unfortunately increasingly common as climate change becomes a tangible reality, often overwhelm the wastewater systems and have caused utilities to pay more than $2 million in fines for Combined Sewer Overflows (CSO) over the last 30 years in New England alone.

The water industry is also not impervious to the data revolution, and a number of firms have developed digital solutions allowing utilities to model their flows and use cutting-edge predictive analytics to optimize the water treatment asset management. Such innovations, when correctly implemented, can allow utilities to save money on operations and maintenance (“O&M”) and schedule their capital expenditures in a manner that reduces risk and uncertainty. However, models are only as good as the data they use, and even if these innovations change the face of the water treatment and distribution industry and dramatically lower water rates, they still require heavy investments to implement the advanced metering infrastructure that will be able to feed models with relevant information. Indeed, old water transmission systems were not designed to measure flows and utilities need to invest in new meters and pumps to be able to collect the data and transmit it.

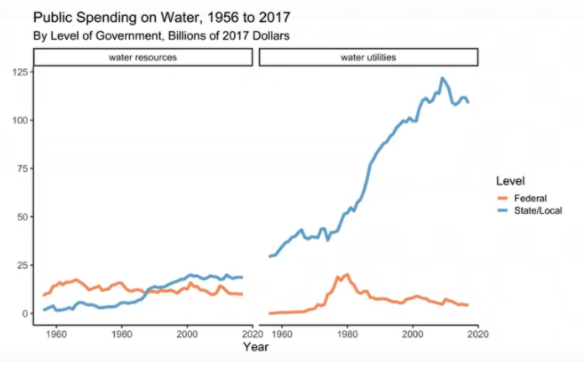

The increasing share of water supply that is handled by private utilities makes little difference when it comes to addressing crumbling infrastructure. Free-market outcomes might not be optimal when it comes to infrastructure provisioning, and the government must often intervene on these markets to make sure the right quantity of these merit goods is supplied. Looking at the distribution of the investments in water and sewer systems across the different levels of government, we see that the cost of capital is mainly borne by local governments and states. Although the Federal State contributes 25% of the total infrastructure spending in the US, its share of investments in water utilities are approximately equal to 3.5%. Additionally, the lawsuits and consent decrees, resulting from the utilities failures such as Flint or the PFAS crisis in North Carolina, have worsened the finances of local governments which are sometimes overwhelmed by compliance costs and lawsuit liabilities.

Image source: Congressional Budget Office

In the short-term, it becomes clear that the Federal Government must either get more involved to help water utilities support their operations and maintenance costs or directly subsidize consumers’ increasing water bills. The policy to support consumers’ water consumption would work in the same way the government does with food through the SNAP program. Giving vouchers to low-income households to help them afford their water bills could help utilities to maintain their level of revenue without directly penalizing less well-off individuals. This redistributive policy could not only lead to greater equity, but could also help water utilities to recover more than their cost and carry out renovation projects.

However, the core problem is the obsolescence of the American water grid, and that need must be addressed. The idea that infrastructure is a “bipartisan issue,” for which politics are not an obstacle, proved to be a misconception under the Trump administration. The error the Trump administration made was to think about the Federal government as a planner that merely needed to raise money to build and own infrastructure. The true role of the federal government is the one of a grant-maker, and the specifics of the project are often better determined at the local scale, far away from Washington D.C. The primary role of local authorities proved to be an obstacle for Trump, as some of his openly anti-immigration declarations have drawn hostility from local officials, alienating him from several key partners. The need for better infrastructure was a theme during the 2020 Presidential race, but the failure of the Trump administration to realize there was a need to shift the role of the federal government to implement a top-down approach sets the challenge for the Biden administration. Currently owning only about 6% of the national infrastructure (BEA estimate), the federal government will have to transition from a grant-maker role to a real infrastructure planner mission to rely less on states and local governments. The challenge facing the Biden administration will be both political and technical: coordinating the forces at all government levels and coming up with clever and economically sound public-private partnerships to finally rejuvenate the American water infrastructure.

Featured Image Source: Capstone Fire & Safety Management

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.