PARMITA DAS – OCTOBER 9TH, 2018

Economic Analysis of the Phenomenon of Child Marriage

Child marriage is defined as marriage taking place before the age of 18. It is deeply entrenched in many communities, so much so that 41,000 girls are married off every day.

According to Human Rights Watch, global data shows that girls from the poorest 20 percent of families are twice as likely to marry before the age of 18 as girls from the richest 20 percent of families. This stems from the traditional perception that girls are financial burdens rather than potential wage earners. Families living in poverty with several children use child marriage as a way to reduce their economic burden. To them, one less daughter means one less person to feed, clothe, and educate. Families often use child marriage as a strategy to evade food insecurity. Girls are even used as a substitute for money to offset debts and settle conflicts. In cultures where the bride’s family is expected to pay a dowry, early marriage equates to a lower bride price. In cultures where the groom’s family pays the dowry in exchange for the bride, younger girls fetch a higher price. The families that cannot afford to raise their daughters may perceive child marriage as the next best alternative and a source of income.

Poverty cements the practice of child marriage. More than half the girls from the poorest families in developing countries are married as children. Families, and often the girls themselves, view marriage as a means to secure their future. The incidence of child marriage increases after humanitarian crises like wars and natural disasters, as families faced with poverty and violence use the practice as a coping mechanism. In fact, nine out of the ten countries with the highest rates of child marriage can be classified as fragile states – developing countries with weak state capacities that are unable to protect their vulnerable citizens.

The article “Child Brides” in the Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization attributes the creation of the conditions that perpetuate child marriage in impoverished societies to parental preference for sons over daughters. Due to a son preference, couples invest fewer resources in caring for their young daughters, so more males survive to traditional marriage age than females. Additionally, to afford to care for the sons they want, some parents dispose of their undesired daughters by marrying them off prematurely. This leads to a sex ratio imbalance, causing some men to turn to younger girls to find a bride. The article analyses data from India to support its theory.

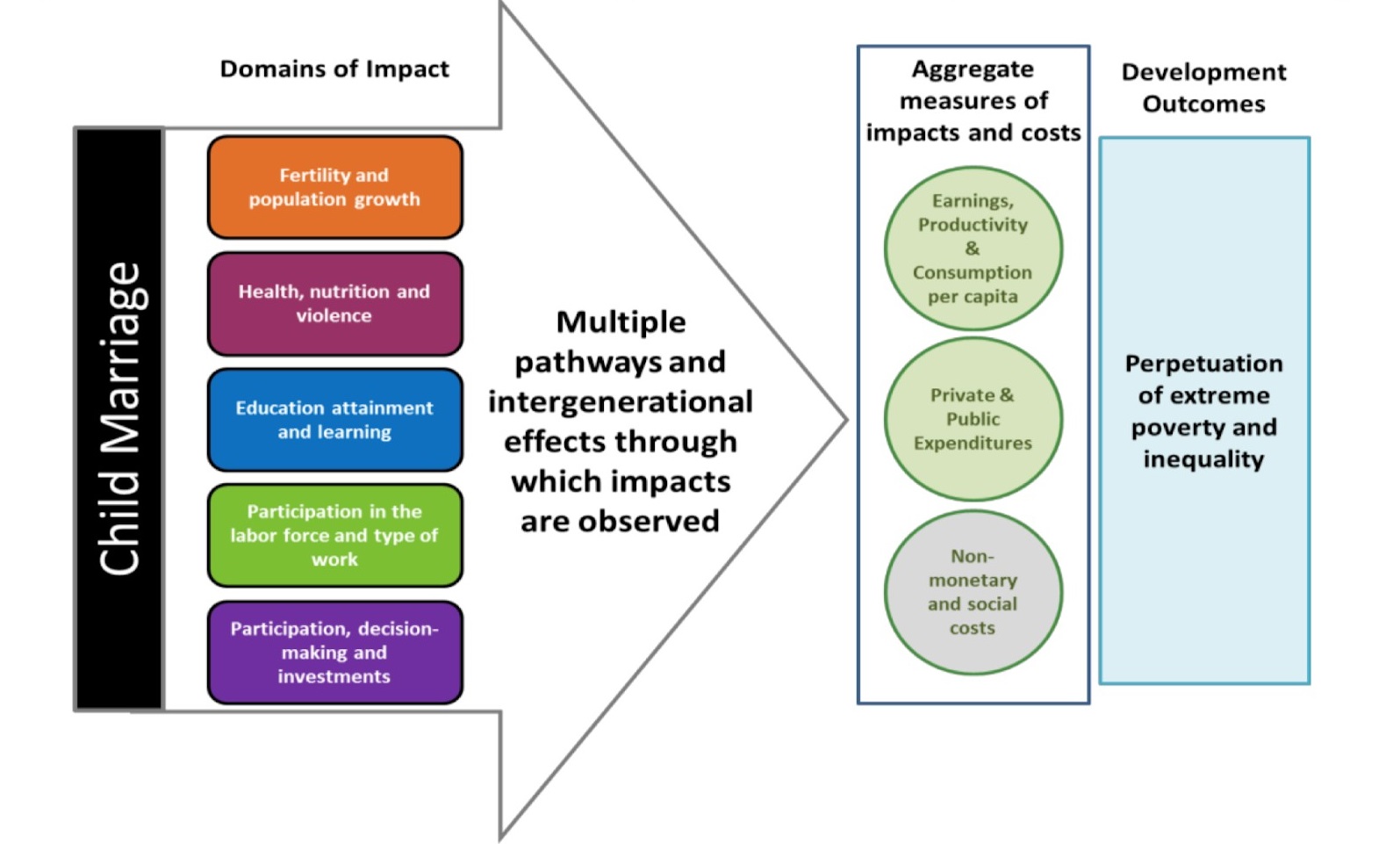

Economic Impacts of Child Marriage

Source: Wooden et al. (2015)

Child marriage disproportionately affects girls; it is a leading cause of school dropouts for adolescent girls. Every year of marriage before 18 reduces the likelihood of completion of secondary school by 4 to 6 percentage points. Child marriage and the associated school dropout rates hamper the girls’ chances of earning better wages by 9 percent over their lifetimes. Female victims often live in poverty, hold jobs less frequently, and are less productive. Child marriage reduces their ability to acquire economic resources and perpetuates their oppression. They have less decision-making and bargaining power in their households and face a higher risk of domestic and intimate partner violence. A direct consequence of child marriage is early childbirths, which contributes to high maternal mortality. Male victims of child marriage may drop out of school early and accept low-paying jobs to support the newly-formed family.

Child marriage engenders high fertility, which yields large costs for families and reduces their standard of living. Having more children reduces a household’s ability to pay for food, education, and healthcare. The alternative to child marriage is having an education, so the opportunity cost deprives households of a potential source of income.

Child marriage is estimated to cost economies at least 1.7 percent of their GDP. It increases total fertility of women by 17 percent, which hurts developing countries battling high population growth. The elevated fertility rates pose significant costs to national economies through demands for basic services by ever-increasing populations. It delays the demographic dividend that can come from reduced fertility and investments in education. The associated cost to the global economy is trillions of dollars in purchasing power parity betweem now and 2030. Child marriage disrupts the accumulation of human capital due to its associated school dropouts, withdrawal from labor markets, and adverse effects on the health of young girls. It perpetuates extreme poverty and hinders efforts to achieve economic growth and equity.

Economic Case for Ending Child Marriage

Ending the practice of child marriage would lead to better prospects for young girls: improved educational attainment, fewer children, increased lifetime expected earnings, improved household incomes, reduced incidence of intimate partner violence, and more decision-making power.

Allowing girls access to higher education changes the prospects of households and the economy for the better. Enabling girls to receive more education increases the likelihood that their children will be educated, thereby improving the human capital of the future labor force of the economy.

Curbing high population growth rates in developing countries would boost economic growth and contribute towards economic stability, saving the global economy $566 billion dollars by 2030. Governments would enjoy budget savings by foregoing the cost of providing basic education, healthcare, and other social services to a rising population. Lower population growth would save governments 5 percent or more of their education budget by 2030. The benefits would be felt strongly by poorer segments of the population and lead to an alleviation of poverty. A 10 percent decrease in child marriages would result in a 76 percent decrease in the maternal mortality rate. The estimated annual benefits for lower under-five mortality and malnutrition is $98 billion by 2030.

The World Bank and International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) carried out a three-year research project titled “The Economic Impacts of Child Marriage” which concluded that ending the practice could save the global economy trillions of dollars by 2030. They believe that understanding the economic benefits would increase the funding by donors and governments towards delaying the age of marriage.

Economic Approaches to Ending Child Marriage

BRAC tackles the practice of child marriage by introducing economic incentives. The NGO teaches financial literacy, entrepreneurship, and banking practices to girls, which allows them to contribute to their households and increase their agency.

The University of Kent developed an overlapping generational model of the marriage market in developing countries by mapping a desirable female attribute whose value decreases with time spent on the marriage market, such that age signals quality. This model demonstrates that, in the absence of intervention, young potential brides have an incentive to accept an offer of marriage sooner than later. Using their model, they showed how large-scale interventions like providing parents incentives to delay their child’s marriage, providing girls new opportunities to acquire skills, and providing alternatives to the traditional path of early marriage can be effective. Some adolescent girls can then turn down marriage to pursue other opportunities or utilize their higher bargaining power to negotiate more favorable marriage offers so it becomes more difficult for men to prey on young, uneducated brides.

Conclusion

The eradication of child marriage has been recognized as a priority by its inclusion in the Sustainable Development Goals. Child marriage perpetuates the cycle of poverty by cutting short girls’ education and limiting their opportunities for employment. It is an example of how a social problem is propagated by financial concerns and, as such, interventions should aim to establish the economic benefits of ending the practice.

Featured Image Source: India Today

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of The Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California at Berkeley in general.